|

Congenital

Malformations of

Uterus and Reproduction

Pankaj

Desai, Sameer Dixit

INTRODUCTION

Developmental

abnormalities of the Müllerian system are one of the most

fascinating conditions in gynecology. A wide range of

abnormalities occur, ranging from mild to severe. Müllerian

abnormalities are associated with renal and axial skeletal

abnormalities and management also involves investigations

and treatment of these conditions.

The earliest reported case of Müllerian abnormality is in

16th century.1 The actual incidence of the Müllerian

abnormalities is unknown. The true incidence may never be

known as these are grossly under reported in childhood and

over reported in the population undergoing infertility

treatment. The incidence varies widely and depends on the

type of study. Most authors report an incidence varying from

0.1–3.5 percent. The most accepted incidence is 4.3 percent

for a general population and fertile women, 3.5 percent for

infertile women and 13 percent in women with recurrent

pregnancy loss.2 In a study of women undergoing Müllerian

assessment at the time of undergoing tubal ligation, an

incidence of 3.2 percent was identified.3

The incidence

also varies with the type of diagnostic test used. In a

study4 of women undergoing HSG for recurrent pregnancy loss,

the incidence was 8–10 percent. With emergence of more

sensitive diagnostic tests, standardized classification and

aggressive management, a more realistic incidence of the

abnormalities would emerge in future.

EMBRYOLOGY OF THE FEMALE GENITAL TRACT

The

reproductive organs of a woman consist of the external

genitalia, the Müllerian tubes and the gonads. All three

develop from different primordial origins and in close

association with the urinary system and the hind gut. In

women, the Müllerian system develops over the Wolffian

system. The cranial parts of the Wolffian system persist as

epoophoron and the caudal parts as the Gartner’s duct. The

Müllerian system persists and forms the adult fallopian

tubes, the uterine corpus, the cervix and part of the

vagina.

At 37 weeks

after fertilization, the Müllerian ducts appear on either

side of the Wolffian duct as invagination of the dorsal

celomic epithelium. The site of the origin remains patent as

the fimbrial end of the Fallopian tubes. The paired

Müllerian tubes grow caudally and medially until they meet

together in the midline and become fused together. They then

converge on the urogenital septum.

The solid

Müllerian tubes undergo simultaneous canalization to form

the tubular structures. The cranial parts which remain

patent and separate evolve into the Fallopian tubes. The

upper fused portions of the tubes form the uterus while the

lowermost fused portion forms the cervix. The vagina is

formed from both the lower end of the fused Müllerian ducts

and the urogenital sinus. The mesenchyme surrounding the

Müllerian ducts condenses to form the musculature of the

female genital tract.

Congenital

abnormalities of the female genital tract occur due to

errors in this developmental process.5 These include:

• Agenesis/Hypoplasia

• Abnormal fusion with urogenital sinus

• Abnormal lateral fusion of the paired Müllerian tubes

• Abnormal resorption of the septum of the fused Müllerian

tubes

Developing kidney and urinary system closely follows

Müllerian system. So, their abnormalities are closely

associated with abnormalities of Müllerian system.

Disruption of developing local mesoderm and somites accounts

for some axial skeletal abnormalities. Cardiac and auditory

defects are occasionally associated. Ovarian morphogenesis

is distinct from Müllerian organogenesis. Hence, in these

conditions, the ovarian function and hormonal milieu is

normal.

GENETICS OF

MÜLLERIAN

ABNORMALITIES

The abnormalities occur due to disruption of the

morphogenesis. Various factors6 have been implicated in

this. These include:

1. Abnormal intrauterine milieu

2. Teratogens like DES and Thalidomide

3. Genetic factors

Genetic

factors involved are complex. They commonly occur

sporadically. If familial incidence is detected then it is

usually multifactorial. Other modalities of inheritance like

autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive and X-linked

disorders also exist.6 Müllerian anomalies may also

represent a part of the multiple malformation syndromes.7

Associated

anomalies are usually seen in cases of Müllerian aplasia (AFS

class I). Associated urological anomalies range between

15–40% in these cases and skeletal anomalies (congenital

absence or fusion of vertebrae) occur in 12–50% of these

cases.8 An association between MRKH syndrome and

Klippel-Fiel syndrome is reported. This syndrome is

characterized by congenital fusion of the cervical

vertebrae, a short neck, low posterior hairline and limited

range of motion in cervical spine.9 The MURCS association (Müllerian

duct aplasia, Unilateral Renal aplasia, Cervicothoracic

Somite dysplasia) is another variant. Infrequently auditory

deficits and cardiac defects can be found. The karyotype of

the females having Müllerian aplasia is 46 XX.

Müllerian

agenesis has been associated with variants of

galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT) enzyme. This

finding suggests that increased exposure to galactose is

responsible for abnormal Müllerian development.10

Other theories about genetic disorders include abnormalities

in MIS (Müllerian Inhibitory Substance) gene, loss of

function mutation in WNT4 gene and abnormalities of

HOXA9-HOXA13 genes. However, none of these have been

consistently associated.

TECHNIQUES

TO ASSESS THE FEMALE GENITAL TRACT

History

In case of MRKH syndrome, the patient may present with

primary amenorrhea. In cases of a bicornuate uterus, patient

may complain of dysmenorrhea. In cases of a vertical vaginal

septum, the patient may come with the complaint that a

tampon is unable to stop menstrual flow. In case of an

obstructive vaginal septum, the patient may complain of

dyspareunia.

Clinical

Examination

Per speculum examination may reveal vaginal septum or

duplication of cervix. Bimanual examination may help in

identifying another horn.

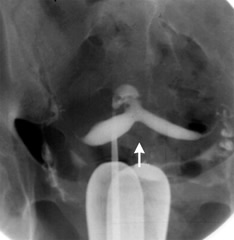

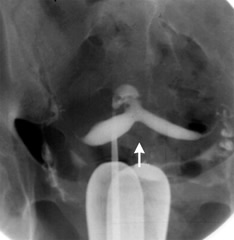

Hysterosalpingography

This has been the classical tool for diagnosis of the

uterine anomalies (Figure 1). When the classic picture of

the uterus with two fallopian tubes is seen, Müllerian

abnormalities are almost ruled out.

Figure 1 HSG

image of bicornuate uterus

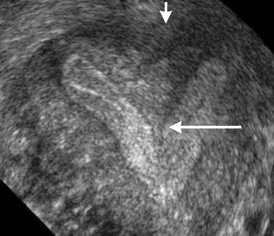

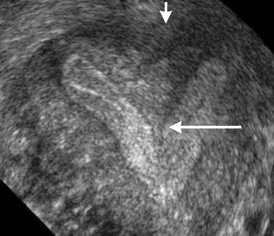

Standard Sonography

In routine

sonography, the key structure to be scrutinized is the

endometrial cavity. In a normal uterus, the endometrial

cavity is single. In a bicornuate uterus, two cavities are

appreciated (Figure 2). It must be noted that it is

difficult to appreciate two cavities in a longitudinal scan.

However, the clinching image is the transverse plane. The

two uterine cavities in a cross section are easily

identified. A TV sonography gives better diagnosis than the

TA sonography. The advantages of sonography are that it is

easily available; it is widely acceptable to the patients

and is relatively cheap. However, the drawbacks are that the

intracavitary lesions are not easily identified, a septum is

not appreciated well and it does not depict the external

contour of the fundus.

Figure 2 Bicornuate

uterus

Saline

Infusion Sonography (SIS)

SIS combines

the USG with HSG. A catheter is placed inside the

endometrial cavity and saline is instilled to achieve

separation of the walls of the endometrial cavity along with

continuous transvaginal ultrasound visualization. It is

usually performed within first 10 days of the cycle. It is

not performed after that period, firstly to avoid aborting

an early pregnancy and secondly, the thick secretary

endometrium may appear wrinkled to give false positive

impression of endometrial pathology.

A balloon

catheter like the pediatric Foley’s is inserted with tip

within the uterine cavity. The balloon is distended with 1ml

of water to prevent backflow of the saline. Slow

instillation of 3 to 10 ml of prewarmed saline is done.

Imaging with transvaginal sonography is done to visualize

separation of the uterine walls (Figure 3). Once adequate

distension is confirmed, a sagittal sweep from cornu to

cornu and an axial sweep from fundus to the cervix are done.

The balloon is then deflated and fluid allowed to flow out.

A second examination with empty uterus is performed. At the

end of the examination, free fluid in the pouch of Douglas

is looked for. Its presence denotes patency of at least one

fallopian tube.

Potential pitfalls include blood clots or mucous plugs

(created by shearing effect of the catheter) being mistaken

for intrauterine pathology or overdistension of the uterus

causing intrauterine pathology to be missed.

Figure 3 SIS

showing uterine cavity

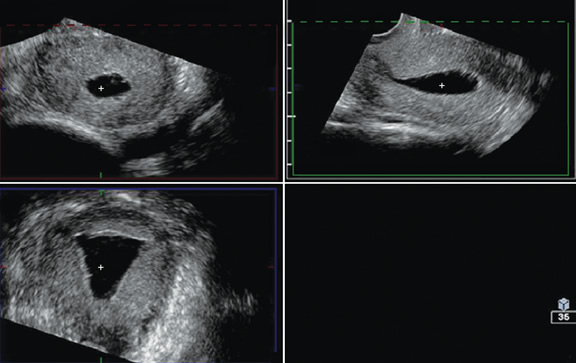

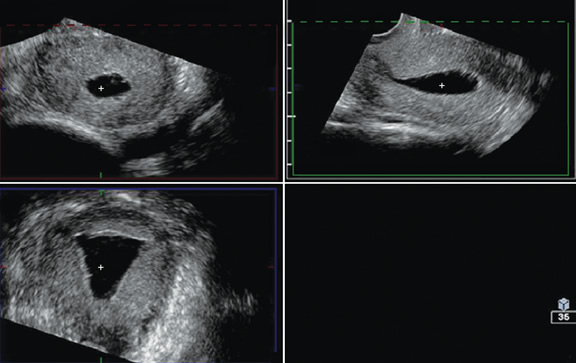

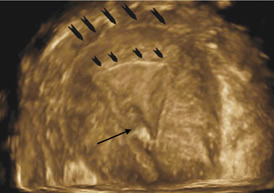

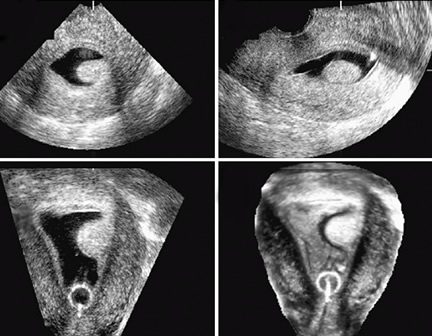

3

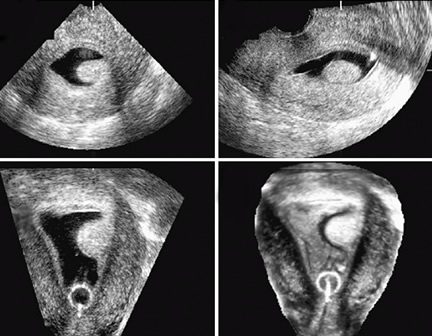

Dimensional Sonography

Conventional 3D sonography or 3D sonography coupled with

saline infusion is better than 2D sonography (Figures 4 to

6). It involves rapid acquisition of data volumes which are

stored for subsequent analysis. Acquisition of the coronal

plane improves diagnosis in almost 30.8 percent of the

patients.11 This includes better evaluation of the external

uterine contour, detection of adhesions and identification

of intrauterine pathologies.

Figures 4A

to D Multiplanar rendering of 3D acquisition showing all

three planes

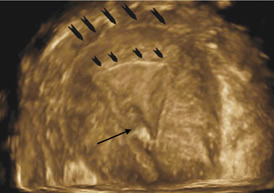

Figure 5 A

3D rendered image. Outer arrows point to the fundus, inner

arrows to endometrial cavity and single arrow to the

catheter tip

Figures 6A

to D 3D Sonography

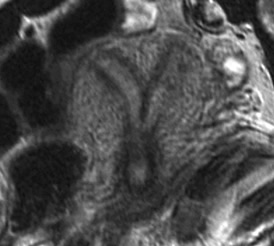

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy allows one to see the fundus of the uterus

from outside. The differentiation between the bicornuate

uterus and the septate uterus is made by the appearance of

the fundus. A septate uterus shows single convex fundus

while a bicornuate uterus shows two cornuae.

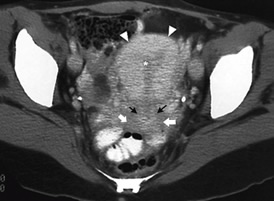

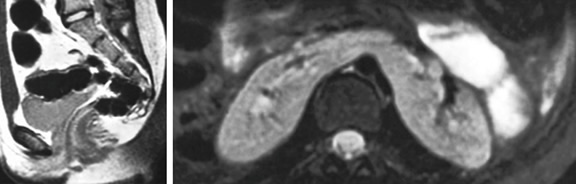

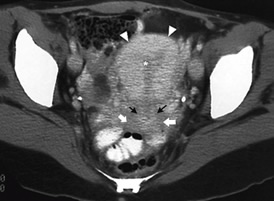

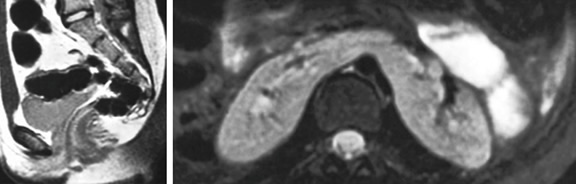

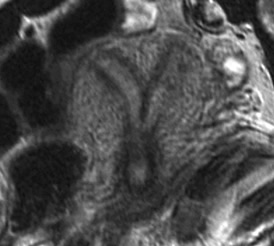

Figures 7 to 9

show Helical CT image of normal uterus, CT image of

bicornuate uterus with horse-shoe kidney, MRI image of

bicornuate uterus and hysteroscopic image of subseptate

uterus respectively.

Figures

7 Helical CT image of normal uterus

Figures 8a

and B CT image of bicornuate uterus (A) with horse-shoe

kidney (B)

Figure 9 MRI

image of bicornuate uterus

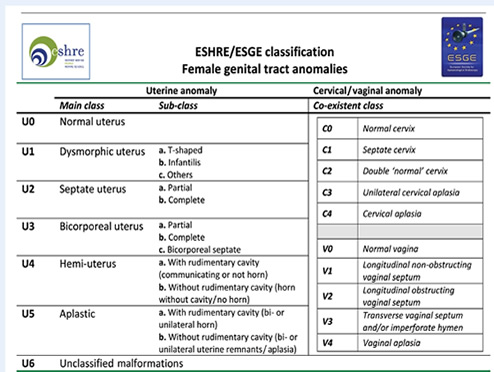

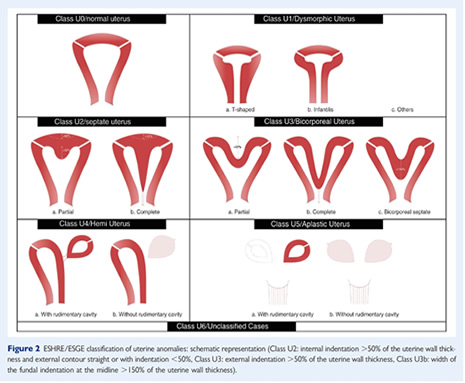

ESHRE/ESGE

consensus on diagnosis of female genital anomalies (21)

Diagnostic Methods:

1. Clinical examination- An essential starting point and

essential part of the evaluation. It also offers unique

evaluation of vaginal and cervical abnormalities

2. HSG- It offers reliable information regarding uterine

anatomy in the absence of cervical obstruction. It can also

provide information regarding cervical can if it is patent.

It however, does not provide any information regarding

anatomy of vagina. It can not be used for diagnosing

obstructive abnormalities. Its efficacy is limited by false

positive and false negatives

3. 2D USG- It is a reliable, objective and measurable tool.

Its an essential part of the assessment. However, it is

dynamic, depends on experience of the clinician. It needs a

systematic approach.

4. Recommendations for proper use of 2D USG- The endometrial

line should always be visible for precise imaging of the

uterus. Serial sagittal and transverse scan should be taken

extending beyond the margins of the uterus.

5. Hysterosalpingo contrast sonography- Early follicular

phase is recommended to avoid pregnancy and artefacts due to

thick secretary endometrium.

6. 3D USG- It can provide highly reliable, objective and,

most importantly, measurable information for the anatomy of

the cervix, uterine cavity, uterine wall, external contour

of the uterus and for associated pelvic pathology; the

coronal plane of the uterus does provide a clear image of

the cavity and the external profile of the uterine fundus.

3D volumes give reliable and objective representation of the

examined organs more independently of the examiner

overcoming the limitations of obtaining coronal images with

2D sonography. It can provide, also, measurable information

even for obstructed parts of the female genital tract.

7. Recommendations for proper use of 3D USG- This method

should be started with a 2D evaluation of the uterus. Use in

mid cycle or luteal phase is encouraged as this demonstrates

the endometrial wall and the outline of the cavity at its

best. Contrast medium could be used for the evaluation of

the cavity and the tubes; in these cases, the examination

has to be performed in the early follicular phase. Save a 3D

volume for off-line analysis. The reconstructed coronal

plane of the uterus might show the cavity and the external

uterine profile as well as the tubal angle and the

junctional zone, if possible along all the endometrium and

cavity. Acquisition of an isolated cervical volume, without

including the uterus: from a mid-sagittal plane, an axial

plane of cervix can be obtained in 80 % and a coronal plane

in 20 %of the cases; in cases of uterine malformations, the

extent of the cervix and the limits of the cervical canal

may be studied better.Diagnosis of associated vaginal

anomalies can be done by trans perineal acquisition of the

pelvic floor volume after filling the vagina with gel or

saline; an axial plane can be obtained from a mid-sagittal

plane.

8. MRI- It is non-invasive and it has no radiation. It gives

a reliable and objective representation of the examining

organs in the sagittal, transverse and coronal plane (three

dimensions). It can be used for diagnosis in cases of

complex and obstructing anomalies. Electronic storage of the

diagnostic procedure is, nowadays, routinely done for

re-evaluation.

9. Hysteroscopy- It is minimally invasive giving the

additional opportunity of treating T-shaped, septate and

bicorporeal septate uterus. Its objective includes

estimation of the cervical canal and endometrial cavity

(differential diagnosis of T-shaped and infantile uterus).

It provides a minimal invasive evaluation of the vagina

and/or cervix in case of virgo. Electronic storage of the

procedure is, nowadays, routinely done for re-evaluation.

10. Endoscopy; laparoscopy and hysteroscopy- It provides

highly reliable information for the anatomical status of the

vagina (vaginoscopic approach), cervical canal, uterine

cavity, tubal ostia, external contour of the uterus and the

intra- peritoneal structures.

11. The invasiveness of the laparoscopic approach makes it

not acceptable as a first-line screening procedure; it

complements indirect imaging in the diagnosis of more

complex anomalies in combination with possible surgical

actions. It offers supplementary information about partial

or total absence of Fallopian tubes and abnormal

localisation of ovaries.

12. Highest degrees of overall diagnostic accuracy were in

de-creasing order: 3D US (97.6 %), sonohysterography (SHG;

96.5 %), 2D US (86.6) and hysterosalpingography (HSG; 86.9

%). MRI was shown to be able to correctly subclassifiy 85.8%

of anomalies. Overall, it appears that 3D US may be more

accurate than MRI in sub-classifying malformations, although

it should be noted that sub-classification is hindered due

to the subjective nature of the previous classifications

adopted.

Uterine wall thickness:

1. Uterine wall thickness is an important parameter and a

reference point for the definitions of dysmorphic T- shaped,

septate and bicorporeal uteri according to the new

classification system. The adoption of an objective

criterion for the definition of uterine deformity is one of

the advantages of the new classification system since

according to AFS classification the detection of anomalies

was based only on the subjective impression of the clinician

performing the test. Although myometrial thickness at the

various uterine regions cannot be easily assessed with

endoscopic techniques, it can be measured with ultrasound or

MRI.

2. Uterine wall thickness- This is the distance between the

line connecting the tubal ostia and the external uterine

profile obtained with 3D US, MRI and, at times, with 2D US

CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS OF THE UTERUS

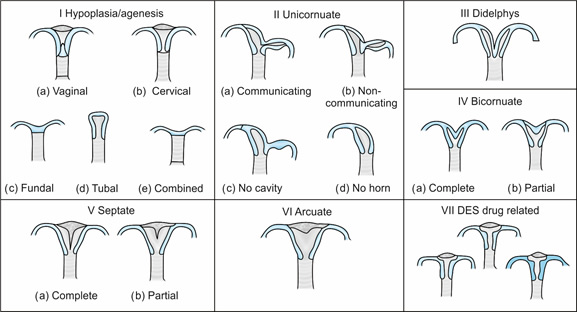

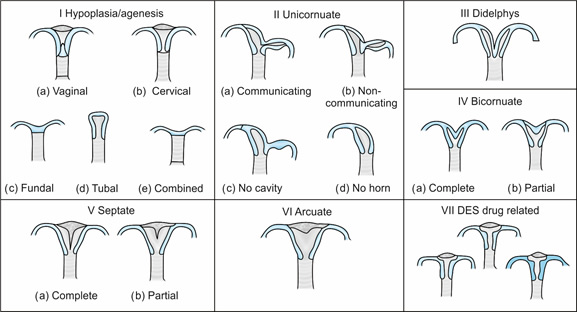

American Fertility Society has classified the

malformations (Figure 10) as:

Figure 10 ASRM classification

of Mϋllerian anomalies

Class I: Agenesis or

Hypoplasia—

Segmental or Complete

Agenesis or hypoplasia may involve the vagina, cervix,

fundus, tubes or any combination of these. Mayor-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser

(MRKH) syndrome is the most well known example of this.

Class II: Unicornuate Uterus

with or

without Rudimentary Horn

When an associated horn is present, this class is

subdivided into communicating (continuity with main uterine

cavity documented) or non-communicating. The

noncommunicating variety is further subdivided on the basis

of whether endometrium is present or absent in the

rudimentary horn. The clinical significance of these types

is that they are invariably associated with ipsilateral

renal and ureteric agenesis.

Noncommunicating accessory horns

that have endometrial cavity are the most common unicornuate

subtype and are clinically important too. They are

associated with high morbidity and mortality. When the

accessory horn becomes obstructed, complication like

hematometra can occur. There is also a risk of developing

endometriosis.

Although normal pregnancies do

occur, this type is associated with poorest obstetrical

performance. This may be due to diminished uterine

vasculature of deficient uterine musculature. A study12 of

393 pregnancies revealed 54.2 percent had normal deliveries,

43.3 percent had preterm deliveries, 4.3% had ectopic

pregnancies and 34.4 percent had spontaneous abortions.

About 2 percent pregnancies occur in accessory horn. Hence

the noncommunicating horn should be excised prior to

pregnancy.

|

|

External contour |

Uterine cavity |

Separation of horns |

Cervix |

|

Normal |

Convex, flat or, 1 cm fundal cleft |

Convex or flat (Two corneal ostia) |

Single triangular cavity |

Single |

|

Unicornuate |

Convex or flat |

Convex or flat (single corneal ostium) |

Single banana shaped cavity |

Single |

|

Didelphys |

Two well formed uterine cornu, convex or flat |

Two well formed uterine cornu with convex fundal

contour in each with no communication |

Two horns widely divergent, at an obtuse angle |

Double |

|

Bicornuate |

Fundal cleft >1cm |

Two well formed symmetric uterine cornu with convex

fundal contour in each fused caudally, communicate |

Two horns widely divergent, at an obtuse angle |

Single or Double |

|

Septate |

Convex, flat or <1 cm fundal cleft |

Two well formed symmetric uterine cornu, communicate |

Two horns close, acute angle at the center |

Single |

|

Subseptate |

Convex, flat or <1 cm fundal cleft |

Two well formed symmetric uterine cornu, communicate |

Two horns close, acute angle at the center |

Single |

|

Arcuate |

Convex, flat or <1 cm fundal cleft |

Single cavity with a broad shallow indentation |

Obtuse angle at the center |

Single |

Class III: Didelphys Uterus

Complete or partial duplication of vagina, cervix and

uterus is a feature of this type.

About 11 percent of all uterine

abnormalities are of this type. Complete type is

characterized by two hemiuteri, two endocervical canals,

with cervices fused at the lower uterine segment. Each

hemiuterus is associated with a fallopian tube. Ovarian

malposition may also be present. The vagina may be single or

double; more commonly double (75%). Occasionally, the

vaginal septum may be transverse.

This type is associated with

renal abnormalities in 20 percent of the cases. A syndrome

called is Wunderlich-Herlyn-Werner syndrome has been

described13. This consists of obstructed unilateral vagina

with uterus Didelphys with ipsilateral ureteric and renal

agenesis.

Class IV: Bicornuate Uterus—Complete or partial

Complete bicornuate uterus is characterized by a uterine

septum that extends from the fundus to the cervical os.

Partial type has a septum which is limited to the fundus. In

both, there is a single cervix and vagina. Obstetric outcome

depends on the length of the muscular septum, i.e. whether

the bicornuate uterus is complete or partial. A partial

bicornuate uterus has a 28 percent incidence of spontaneous

abortion while in case of a complete bicornuate uterus; the

incidence of abortion is 66 percent.

Class V: Septate Uterus—Complete or partial

A single uterus has a complete or partial septum. The

septum is located in the midline fundal region. It is made

up of poorly vascularized fibro muscular tissue. There are

various variations of the septum. Sometimes a complete

septate uterus is associated with a septate vagina. A

variant septate abnormality exists which is characterized by

the triad of complete septate uterus, duplicated cervix and

septate vagina.14 It is undistinguishable from uterus

Didelphys except by doing laparoscopy or a 3D USG. On

laparoscopy, it is identified by its convex external

contour.

A rare variant of septate uterus is Robert uterus.15 This

is characterized by a complete septum and a noncommunicating

hemiuteri with a blind horn.

Patients with a septate uterus have no difficulty in

conceiving. Yet, they have poorest reproductive outcome of

all the Müllerian anomalies.

Class VI: Arcuate Uterus

A small septate indentation is seen at the fundus.

Class VII: DES Related Abnormalities

A “T” shaped uterine cavity is seen.

Defects Not Classified by the AFS

• Transverse vaginal septum

• Vaginal Atresia

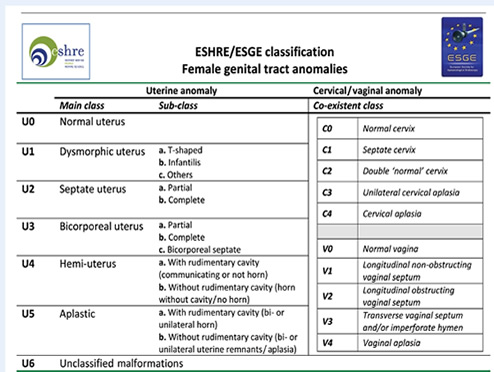

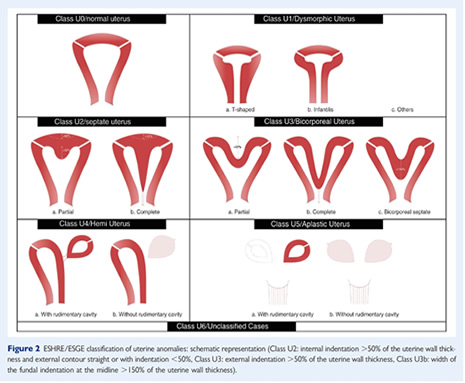

The ESHRE/ESGE classification

It was believed that the existing AFS classification had

limitations (20). There was need to have a classification

that was:

1. Clear and accurate

2. Which correlated with patient management

3. was simple

and friendly

MANAGEMENT

Müllerian Aplasia

This basically includes management of vaginal agenesis

or MRKH syndrome. Here, the management comprises of two

parts:

1. Creation of neovagina

2. Fertility treatment

Creation of Neovagina

Two methods have been described, nonsurgical and

surgical. The nonsurgical method basically involves use of

prosthetic moulds which deepen the existing pouch to create

a satisfactory space for coitus. While surgical methods

involve creation of neovagina, the strategy is to develop a

space between the rectum and the bladder. Various tissues

have been used to cover the newly created space. Full

thickness or part thickness skin grafting is the most

popular technique. However, skin grafting is associated with

scar formation or contractures. Alternately, human amnion,

not stripped from chorion is used as a graft material.16

More elaborate plastic surgical techniques include use of

transposition flaps and autologous buccal mucosa. Use of

artificial dermis and absorbable adhesion barrier shows

promise as exogenous graft material to be used in neovagina.

Interceed (Ethicon) has been used as an absorbable adhesion

barrier. The neovagina epithelializes within 1 to 4 months.

Some surgeons use a bowel segment in place of skin graft.

However, this is associated with troublesome leucorrhea

after the surgery.

Fertility Treatment

Since, most of these women have healthy and functioning

ovaries; surrogate pregnancy is a viable treatment modality.

Unicornuate Uterus

The indication for surgery is presence of endometrium in

the rudimentary horn. In case the rudimentary horn does not

have a functioning endometrium, then surgical intervention

is not indicated.

In case surgery is contemplated, laparoscopic

hemihysterectomy of the rudimentary horn is the procedure of

choice. The rudimentary horn is connected to the functioning

unicornuate uterus by a fibromuscular band. This band is of

importance as the uterine artery courses inferior to it. The

pedicle of the rudimentary horn is coagulated using bipolar

cautery. Tube and the rudimentary horn are removed, leaving

ipsilateral ovary which is usually healthy, in situ.

In the event of pregnancy in the rudimentary horn, same

procedure as nonpregnant uterus is followed. However, there

is a risk of increased bleeding due to pregnancy related

vascularization. Methotrexate has been used to treat the

pregnancy before surgical removal of the rudimentary horn.

Hysteroscopic endometrial ablation of the rudimentary

horn has been reported.17

Uterus Didelphys

Guidelines for surgical intervention are as follows:

1. Uterus didelphys with obstructive vaginal septum—Full

excision and marsupialization of the vaginal septum is the

treatment of choice. After the septum is excised,

laparoscopy may be indicated as these cases are associated

with endometriosis.

2. Uterus didelphys with nonobstructive vaginal

septum—surgery is indicated if the patient complains of

dyspareunia.

3. Currently, metroplasty is not indicated in cases of

nonobstructive didelphys uterus.

Bicornuate Uterus

Guidelines for surgical correction are as follows:

1. Bicornuate uterus seldom requires surgical management.18

2. Metroplasty should be reserved for those women with

repeated pregnancy losses or rarely in those in whom no

other cause for infertility is detected.

Septate Uterus

Uterine septum is associated with primary infertility,

recurrent miscarriages and preterm labor. In such cases,

hysteroscopic resection of the septum is indicated.19 The

decision to operate should be taken only for poor

reproductive performance.

ESHRE/ESGE consensus on workup of female genital

anomalies (21)

Recommended evaluation of asymptomatic women

Clinicians should, always, be attentive for the presence of

a congenital anomaly in asymptomatic women of reproductive

age during their routine examination, supplementing

gynaecological examination with a 2D US as follows:

Gynecological examination: the anatomy of the external

genitalia, the vagina and the cervix should be carefully

evaluated.

2D US: it should be done in a pre-defined and systematic

manner to increase its diagnostic accuracy. The shape and

the dimensions of the uterine cavity, the uterine wall

(anterior, posterior, lateral and fundal width) and external

uterine contour should be recorded in a systematic way in

longitudinal and transverse planes.

The absence of findings suspicious for the presence of an

anomaly should not be considered as definite and the

presence of one could not be excluded.

Positive findings should be used for documentation only

and counselling of the patients for further investigation

given that they are asymptomatic women.

Recommended evaluation of symptomatic women

Gynecological examination with careful evaluation and

recording of the external genitalia, vaginal and cervical

anatomy.

2D US (vaginal) in a pre-defined and systematic manner

(to increase its diagnostic accuracy), where the shape and

the dimensions of the uterine cavity, the uterine wall

(anterior, posterior, lateral and fundal width) and external

uterine contour should be recorded in a systematic way and

pre-defined way in longitudinal and transverse planes.

Measurements of 2D US examination should be used as a

referendum for the evaluation of uterine anatomy deviations

in 3D ultrasound.

3D US (vaginal) in a pre-defined and systematic manner

where the shape and the deviations from normal cervical and

uterine anatomy should be recorded and documented.

REFERENCES

1. Steinmetz GP. Formation of artificial vagina. West J

Surg 1940; 48: 169-73.

2. Grimbizis GF, Camus M, Tarlatzis BC, Bontis JN, Devroey

P. Clinical implications of uterine malformations and

hysteroscopic treatment result. Hum Reprod Update 2001; 7:

161-74.

3. Frank R. The formation of an artificial vagina without

operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1938; 35: 1053-5.

4. Stray-Pederson B, Stray-Pederson S. Etiologic factors and

subsequent reproductive performance in 195 couples with a

prior history of habitual abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1984; 148: 140-46.

5. Amesse LS, Pfaff-Amesse T. Congenital anomalies of the

reproductive tract. [book auth.] Hurd WW, Falcone T.

Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. New York:

Elsiever 2000; pp 235-9.

6. Golan A, Langer R, Bukovsky I, Caspy E. Congenital

Anomalies of Müllerian System. Fertil Steril 1989; 5:

747-55.

7. Carson SA, Simpson JL, Elias S, Gerbie AB, Buttram VC Jr,

et al. Heritable aspects of uterine anomalies. Fertil Steril.

1983; 1: 86-90.

8. Turunen A, Unnerus CE. Spinal changes in patients with

congenital aplasia of the vagina. 46, 1967, Acta Obstet

Gynecol Scand 1967; 1: 99-106.

9. Willemsen WN. Combination of Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster and

Klippel Fiel syndrome-a case report and literature review.

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1982; 4: 229-35.

10. Aughton DJ. Müllerian duct abnormalities and

galactosemia heterozygosity: report of a family. Clin

Dysmorphol 1993; 1: 55-61.

11. Erdem M, Bilgin U, Bozkurt N, et al. Comparison of

transvaginal sonography and saline infusion

sonohysterography in evaluating the endometrial cavity in

pre and post menopausal patients with abnormal uterine

bleeding. Menopause. 2007; 14: 846-52.

12. C Lin P. Reproductive outcomes in women with uterine

anomalies. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2004; 1: 33-9.

13. Tridenti G, Bruni V, Ghirardini G. Double uterus with

blind hemivagina and ipilateral renal agenesis: clinical

variants in three adolescent women.case report and

literature review. Adolesc Pediatric Gynecol 1995;8: 20.

14. Giraldo JL, Habana A, Duleba AJ, Dokras A. Septate

Uterus associated with cervical duplicationand vaginal

septum. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc, 2000; 2: 277-9.

15. Robert HG. Uterus cloisonne avec cavite borgne sans

hematometeri. CR Soc Fr Gynecol, 1989; 767-7.

16. Nisolle M, Donnez J. Vaginoplasty using amniotic

membranes in cases of vaginal agenesis or after vaginectomy.

J Gynecol Surg 1992; 1: 25-30.

17. Hucke J, DeBruyne F, Campo RL, Freikha AA. Hysteroscopic

treatment of congenital uterine malformations causing

hemihematometra: a report of three cases. Fertil Steril, 58:

823-57.

18. Jones HW. Reconstruction of congenital uterovaginal

anomalies. [book auth.] Murphy AA, Jones HW Rock JA. Female

Reproductive Surgery. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and

Wilkins 1992, 246.

19. Valdes C, Malini S, Malinak LR. Ultrasound evaluation of

female genital tract abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol,

1984; 149: 285-92.

20. Grimbizis, G. F., Gordts, S., Di Spiezio Sardo, A.,

Brucker, S., De Angelis, C., Gergolet, M., … Campo, R.

(2013). The ESHRE-ESGE consensus on the classification of

female genital tract congenital anomalies. Gynecological

Surgery, 10(3), 199–212. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-013-0800-x

21. Grimbizis, G. F., Di Spiezio Sardo, A., Saravelos, S.

H., Gordts, S., Exacoustos, C., Van Schoubroeck, D., …

Campo, R. (2016). The Thessaloniki ESHRE/ESGE consensus on

diagnosis of female genital anomalies. Gynecological

Surgery, 13(1), 1–16. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-015-0909-1 |