| |

|

|

RECURRENT PREGNANCY LOSS

By:

• DR. PANKAJ DESAI

Dean (Students) and Assoc.

Professor [VRS]

Dept. Of Obstetrics & Gynecology

Medical College & S. S. G. Hospital

BARODA

• DR. MONA SHROFF

Fmr. Asst. Professor

Dept. Of Obstetrics & Gynecology

Surat Municipal Institute of Medical Education and Research

SURAT

INTRODUCTION:

A pregnancy loss (miscarriage) is defined as the

spontaneous demise of a pregnancy before the fetus reaches

viability. The term therefore includes all pregnancy losses

from the time of conception until 24 weeks of gestation (20

weeks in few countries with advanced neonatal care

infrastructure).Majority of these sporadic losses are due to

random numeric chromosomal errors.

Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) is one of the most

emotionally traumatic, disconcerting and challenging areas

in reproductive medicine because the etiology is often

unidentified and research on the etiology, evaluation, and

management of RPL is often erroneous. Typical methodological

shortcomings include failure to adhere to generally accepted

criteria for RPL, improper selection of controls,

ascertainment bias ,disparate monitoring of cohorts, no

exclusion of aneuploid fetuses, lack of stratification for

important factors such as number of previous losses,

premature termination of study after interim analysis, and

excessive post-randomization patient withdrawal [1].

DEFINITION:

The definition of RPL is varied which makes research on

evaluation, management and counselling more challenging.

●Two or more failed clinical pregnancies as documented by

ultrasonography or histopathologic examination [2].

●Three consecutive pregnancy losses, which are not required

to be intrauterine [3-6].

Non-visualized pregnancy losses (biochemical pregnancy

losses and/or pregnancies of unknown location) had the same

negative impact on future live birth as an intrauterine

pregnancy losses. These definitions also do not take into

account the effect of maternal age or the gestational age at

which the miscarriage occurred.

RPL can be further divided into primary or secondary.

Primary RPL refers to pregnancy loss in women who have never

carried to viability. Secondary RPL refers to pregnancy loss

in a woman who has had a previous live birth. The prognosis

for successful pregnancy is better with secondary RPL [7, 8]

Further classification can be Pre-embryonic (<4 weeks),

Embryonic (5-9 weeks), and Fetal (>10 weeks)

INCIDENCE:

Approximately 15 percent of pregnant women experience

sporadic loss of a clinically recognized pregnancy. Just 2

percent of pregnant women experience two consecutive

pregnancy losses and only 0.4 to 1 percent have three

consecutive pregnancy losses [9). At very early gestational

ages (e.g., at less than 6 weeks of gestation) the risk of

miscarriage is 22 to 57 percent versus 15 percent at 6 to 10

weeks and 2 to 3 percent after 10 weeks [10, 11]). The

prevalence of miscarriage is higher with increasing maternal

age, most likely due to poor oocyte quality (12)

TABLE I: Age and chances of Miscarriage

|

Age(Yrs.) |

Spontaneous Miscarriage risk (%) |

|

Overall |

11 % |

|

20-30 yrs. |

9-17% |

|

35 yrs. |

20% |

|

40 yrs. |

40% |

|

45 yrs. |

80% |

RISK FACTORS AND ETIOLOGY:

RPL is a heterogeneous condition, with numerous causes,

diverse treatment options and enormous psychological

implications. It is multidisciplinary, involving gynecology,

genetics, endocrinology, immunology, pediatrics and internal

medicine.

Two major concerns for the physician and the couple are:

the cause and the risk of recurrence. The etiology can be

identified in less than 50 percent of patients. General

etiological categories of RPL include anatomic,

immunological, genetic, endocrine, infectious, thrombophilic,

male factors and environmental factors. Prognosis is based

on the number of preceding pregnancy losses and female age.

Previous pregnancy loss — (13)

Table II: Number of previous Losses and risk of

miscarriage

|

Number of previous losses |

Risk of miscarriage (%) |

|

Zero |

11-13 |

|

1 |

14-21 |

|

2 |

24-29 |

|

3 |

31-33 |

Genetic factors

• Parental chromosomal rearrangements [14, 15] in 2–5%

of couples with recurrent miscarriage, one of the partners

carries a balanced structural chromosomal anomaly, most

commonly a balanced reciprocal or Robertsonian translocation

less commonly, an inversion. Although carriers of a balanced

translocation are usually phenotypically normal, their

pregnancies are at increased risk of miscarriage or

congenital malformations and/or mental disability secondary

to an unbalanced chromosomal arrangement. The risk of

miscarriage is influenced by the size and the genetic

content of the rearranged chromosomal segments. Balanced

translocations are more common in the females likely to

result in pregnancy loss if the translocation is of maternal

origin.

• Chromosomal abnormalities of the embryo [16-17].

— In couples with RPL aneuploidies account for 30–57% of

further miscarriages. The risk of aneuploidy and association

with the number of previous miscarriages is contradictory in

several studies but mostly as the number of miscarriages

increases, the risk of euploid pregnancy loss increases. The

relationship between the karyotype of the abortus and risk

of RPL requires further study to better define which

abnormalities are likely to be recurrent. Recurrent

aneuploid losses may be associated, in part, with the older

age of the mothers.

The likelihood that RPL is related to parental karyotypic

abnormality is higher when:

• Young maternal age at second miscarriage.

• History of three or more miscarriages.

• History of two or more miscarriages in a sibling or the

parents of either partner

• A family history of stillbirth or an abnormal live--born.

Immunologic factors:

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) (18, 19) — several

autoimmune diseases have been linked to poor obstetric

outcome, but APS is the only immune condition in which

pregnancy loss is a diagnostic criteria for the disease.

Five to 15 percent of patients with RPL may have APS

compared to 2% in normal obstetric patients. APS is the most

important treatable cause of recurrent miscarriage

The mechanisms by which antiphospholipid antibodies cause

pregnancy morbidity include inhibition of trophoblastic

function and differentiation, activation of complement

pathways at the maternal–fetal interface resulting in a

local inflammatory response and thrombosis of the

uteroplacental vasculature.

Other immunological factors (20-23) — allogeneic factors

may cause RPL by a mechanism similar to that of graft

rejection in transplant recipients. If the blastocyst is

developmentally normal and intact, the embryo is entirely

protected by trophoblast cells. In some pregnancies, the

blastocyst is genetically deformed and not fully intact so

paternally-derived antigens are exposed to the maternal

immune system, leading to a rejection response. A secondary

immune response would be expected to cause early rejection

in cases of RPL.

Alternatively, some mothers with RPL may lack essential

components of the networks that provide immunological

protection to the embryos, such as appropriate expression of

complement regulatory proteins. Deregulation of the normal

immune mechanism, although not well defined, probably

operates at the maternal-fetal interface and may involve

increased activity of uterine natural killer (uNK) cells,

which appear to regulate placental and trophoblastic growth,

local immunomodulation, and control of trophoblastic

invasion.

Thrombophilia and fibrinolytic factors[24-25] —

Thrombosis of spiral arteries and the intervillous space on

the maternal side of the placenta can impair adequate

placental perfusion leading to late fetal loss, FGR,

placental abruption, or preeclampsia. A relationship to

early pregnancy loss is conflicting and may be restricted to

specific thrombophilic defects that have not been fully

defined, or the presence of multiple defects. A systematic

review of the association between fibrinolytic defects and

RPL found a significant association for factor XII

deficiency.

Procoagulant microparticles can also contribute to the

hypercoagulable state and likely to interfere with

successful implantation and fetal growth. These were shown

to be associated with early and late unexplained pregnancy

loss.

Uterine factors [26-33]. — Acquired and congenital

uterine abnormalities are responsible for 10 to 50 percent

of RPL.

Anomalies — Congenital uterine anomalies are

present in 10 to 15 percent of women with RPL versus 7

percent of all women but there is a wide variability in

diagnosis and inclusion criteria (first/second trimester)

Pregnancy loss may be related to impaired uterine distention

or abnormal implantation due to decreased vascularity in a

septum, increased inflammation, or reduction in sensitivity

to steroid hormones with possibly coexisting cervical

weakness. The septate uterus is the most common uterine

abnormality associated with RPL and the poorest reproductive

outcome due mechanisms not clearly understood. The

miscarriage rate in women with untreated septum in small

observational studies is greater than 60 percent. The longer

the septum, the worse the prognosis possibly due to poor

blood supply and implantation. Arcuate uteri are more

associated with second trimester losses.

Leiomyoma — Submucous leiomyomas that protrude

into the endometrial cavity can impede normal implantation

as a result of their position, poor endometrial receptivity

of the decidua overlying the myoma, or degeneration with

increasing cytokine production but no clear association has

been proven.

Endometrial polyps — there have been no data

showing a relationship between endometrial polyps and RPL.

Intrauterine adhesions — intrauterine adhesions

or synechiae lead to pregnancy loss because there is

insufficient endometrium to support fetoplacental growth.

The main cause of intrauterine adhesions is intrauterine

interventions traumatizing the basalis layer, leading to

menstrual irregularities (hypomenorrhea, amenorrhea), cyclic

pelvic pain, infertility, and RPL.

Cervical insufficiency — cervical insufficiency

could lead to recurrent midtrimester, but not early

pregnancy loss. True incidence remains unknown due to

essentially a clinical diagnosis and no specific

inter-pregnancy test

Defective endometrial receptivity — Estrogen and

progesterone prepare the endometrium for pregnancy. Normal

endometrial receptivity allows embryo attachment,

implantation, invasion, and development of the placenta.

These processes are likely to be disturbed when endometrial

receptivity is defective, resulting in unexplained

infertility and RPL. Causes of defective endometrial

receptivity and biomarkers for evaluation of endometrial

receptivity are under research. RPL may be associated with

primary receptor defect, uterine stem cell deficiency and

enhanced cellular senescence, which then results in abnormal

endometrial preparation leading to RPL.

Environmental chemicals and stress (21, 34)—There

is no high-quality evidence showing a relationship between

RPL and occupational factors, stress, or low level exposure

to most environmental chemicals. Chemicals that have been

associated with sporadic spontaneous pregnancy loss include

anesthetic gases, arsenic, aniline dyes, benzene, ethylene

oxide, formaldehyde, pesticides, lead, mercury, and cadmium.

Other

Personal habits [1, 35] — the association between RPL

and obesity, smoking, alcohol use, and caffeine consumption

is unclear. These factors may act in a dose-dependent

fashion or synergistically to increase the rate of sporadic

pregnancy loss.

Male factor [36-38]. — There is a trend toward

repeated miscarriages in women whose male partner has

abnormal sperms (e.g., poor morphology, sperm chromosome

aneuploidy, high DFI) advanced paternal age may be a risk

factor for miscarriage.

Infection[39-41] — Some infections, such as

Toxoplasma gondii, cytomegalovirus, and primary genital

herpes, are known to cause sporadic pregnancy loss, but no

infectious agent has been proven to cause RPL. The presence

of bacterial vaginosis in the first trimester of pregnancy

has been reported as a risk factor for second-trimester

miscarriage and preterm delivery, but the evidence for an

association with first trimester miscarriage is

inconsistent.

Decreased ovarian reserve[42] — Women with

unexplained RPL have a higher incidence of abnormal ovarian

reserve tests, than women with a known cause of RPL Women

with RPL and elevated day 3 FSH or low AMH may have poor

quality oocytes that fail to develop after fertilization.

Future research [43-45] — A meta-analysis of

studies evaluating whether there is an association between

cytokine polymorphisms and RPL concluded there was no more

than a mild non-significant association. Progesterone

receptor gene polymorphisms, as well as other gene

polymorphisms, may play a role in RPL.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION:

The minimum diagnostic workup of couples with RPL

consists of a complete medical, surgical, genetic, and

family history and a physical examination.

History — the history should include

• The gestational age and characteristics (e.g., anembryonic

pregnancy, live embryo) of all previous pregnancies.

Gestational age is important because RPL typically occurs at

a similar gestational age in consecutive pregnancies and the

most common causes of RPL vary by trimester. E.g.

Miscarriages related to chromosomal and endocrine defects

tends to occur earlier in gestation than losses due to

anatomic or immunological abnormalities; however, there is

significant overlap.

• Abnormalities in menstrual cycle length may be due to

endocrine dysfunction. Presence of galactorrhea, which also

suggests endocrine dysfunction (hyperprolactinemia)

• Does the family history display patterns of disease

consistent with a strong genetic influence? Is consanguinity

present?

• Was embryonic/fetal cardiac activity ever detected? RPL

prior to detection of embryonic cardiac activity also

suggests a chromosomal abnormality

• Is there exposure to environmental toxins, which may be

lethal to developing embryos?

• Is there a personal/family history of venous or arterial

thrombosis suggestive of antiphospholipid syndrome?

• History of uterine instrumentation, which may have caused

intrauterine adhesions.

• What information is available from previous laboratory,

pathology, and imaging studies?

Physical examination — Physical assessment should

include signs of endocrinopathy (e.g., hirsutism,

galactorrhea) and pelvic organ abnormalities (e.g., uterine

malformation, cervical laceration).

Mental health evaluation — screening for severe stress and

depression should be an integral part of the RPL work-up.

EVALUATION:

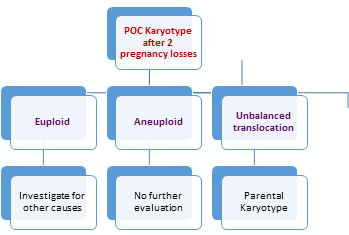

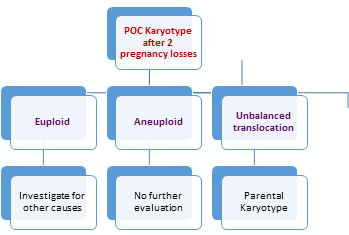

Parental Karyotype [16, 21, 46] — Karyotyping of couples is

part of the evaluation of RPL, despite the low yield of

abnormality, cost, and limited prognostic value. The purpose

is to detect balanced reciprocal or Robertsonian

translocations or mosaicism that could be passed to the

fetus unbalanced.

Karyotype of the abortus or products of conception [16,

47] -- Chromosomal abnormalities detectable in parental

peripheral blood preparations are an indirect and limited

indicator of fetal karyotype vis-a-vis the fetal karyotype.

• Knowledge of the karyotype of the products of

conception allows an informed prognosis for a future

pregnancy outcome

• To differentiate whether it was sporadic due to abnormal

embryo or treatment failure per se and need for further

evaluation

• A normal karyotype suggests (but does not prove) a

maternal factor as the cause of pregnancy loss, while an

abnormal karyotype is usually a sufficient explanation for a

nonviable pregnancy

• If the karyotype of the miscarried pregnancy is

abnormal(Aneuploidy), there is a better prognosis for the

next pregnancy(except unbalanced translocations)

Pitfalls of conventional POC karyotype are: - [48-50].

• Failure to cultivate: Cells from chromosomally abnormal

abortuses, are less likely to grow in culture, thereby

skewing the results of cohort studies maternal tissue

contamination. Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH)

does not require dividing cells, and therefore can be useful

in fetal demise with culture failure.

• Failure to seek other coexisting causes if cytogenetic

study reveals chromosomal abnormality.

• Occurrence of non-cytogenetic embryonal abnormalities.

• Type of laboratory and analysis: In some cases, karyotype

analysis of the abortus indicates a normal chromosomal

pattern, but more detailed Acgh demonstrates major

abnormalities.

• Need for surgical evacuation.

Fig I: Flow Chart for

Evaluation of Chromosomal Anomalies in RPL

Uterine assessment [51-57].— Anatomic causes of

RPL are usually diagnosed using hysterosalpingography (HSG)

, sonohysterography.(SHG) or 3D ultrasound(USG) .3D USG and

SHG are more accurate than HSG in delineating internal

contours along with outer. Ultrasound (especially 3D) is

useful for making the diagnosis of a septate/arcuate/bicornuate

uterus ,renal abnormalities associated, the presence and

location of uterine myomas and, in pregnancy, the

possibility of cervical insufficiency and assessment of

fetal viability.

Hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, or magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) due to invasiveness and /or cost, are used as

second-line tests when additional information or therapeutic

intervention is required.

Anticardiolipin antibodies and lupus anticoagulant

[58-60]— The minimum immunology work-up for women with

RPL is measurement of anticardiolipin antibody (IgG and IgM)

and lupus anticoagulant, done twice, six to eight weeks

apart, because a low to mid positive level can be due to

viral illness and revert to normal. The anticardiolipin

antibody titre is considered elevated if medium or high

titres of both IgG and IgM isotypes are present in blood.

The detection of the lupus anticoagulant is generally based

upon an activated partial thromboplastin time, kaolin plasma

clotting time, or dilute Russell viper venom test time

Table III: Clinical and Laboratory Findings in

Reproductive Autoimmune Syndrome

|

|

Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) |

Reproductive Autoimmune Failure Syndrome (RAFS) |

|

Clinical features |

·

Thrombosis (≥1 unexplained

venous or arterial thrombosis, including stroke) |

·

FGR(<34 weeks) |

|

·

Autoimmune thrombocytopenia |

·

Severe Preeclampsia |

|

·

Adverse Pregnancy outcome |

·

Obstetric complications

(abruption placenta, chorea gravidarum, HELLP

syndrome) |

|

|

·

Unexplained infertility |

|

o

Three or more consecutive miscarriages before 10

weeks of gestation |

·

Endometriosis |

|

o

One or more morphologically normal fetal losses

after the 10th week of gestation |

·

Recurrent pregnancy loss |

|

o

One or more preterm births before the 34th week of

gestation owing to placental disease. |

o

≥1 consecutive and otherwise unexplained fetal

deaths (≥10 weeks) |

|

|

o

≥3 consecutive and otherwise unexplained

preembryonic or embryonic pregnancy losses |

Thyroid function [61-63] — Thyroid function should

be assessed if positive history or symptoms. Screening

asymptomatic women for subclinical thyroid dysfunction is

controversial but recommended since there is evidence of an

increased risk of miscarriage in women with subclinical

hypothyroidism and in euthyroid women with thyroid

peroxidase (TPO) antibodies.

Hypercoagulable state —Evaluation for an inherited

thrombophilia can be considered in rare cases of recurrent,

unexplained late fetal loss (after nine weeks of gestation)

associated with evidence of placental ischemia and

infarction and maternal vessel thrombosis.

Culture and serology [21]. — Routine cervical

cultures are not useful in the evaluation of RPL among

otherwise healthy women.

Autoantibodies and immune function [64-74]. — Many

studies have reported the presence of autoantibodies in

women with RPL .The pregnancy outcome of women with and

without antinuclear antibody (ANA) is the same hence routine

testing for ANA not recommended. Peripheral blood NK cells

are phenotypically and functionally different from uterine

NK (uNK) cells. There is no clear evidence that altered

peripheral blood NK cells are related to recurrent

miscarriage. Examining the relationship between uNK cell

numbers and future pregnancy outcome remains a research

field. Selection of appropriate tests for diagnosis of

immune-based RPL (HLA typing, mixed lymphocytotoxic antibody

tests, CD56+ cells and cytokine polymorphism) also requires

further investigation and validation.

Screening for diabetes — limited to women with

clinical manifestations of the disease.

Progesterone level [75] — Single or multiple serum

progesterone levels are not predictive of future pregnancy

outcome.

Endometrial biopsy [76] for luteal phase defect is

not predictive of fertility status and not recommended.

MANAGEMENT:

RPL is an inhomogeneous condition and hence specific

guidelines cannot be applicable in general to all. The

development of an optimal investigation and management

protocol depends on reaching a correct diagnosis of etiology

and directing specific treatment. Therapeutic

recommendations are largely based upon clinical experience

and data from observational studies. The overall live birth

rates after normal and abnormal diagnostic evaluations for

RPL are 77 and 71 percent, respectively [77].In all cases,

psychological support is vital[78,79].

• PARENTAL KARYOTYPE ABNORMALITY [80-85] — Couples

in whom chromosomal abnormalities are discovered in one or

either partners or the abortus are generally referred for

genetic counselling. They should receive information

regarding the probability of having a chromosomally normal

or abnormal conception in the future... The magnitude of

these risks varies according to the specific chromosomal

abnormality and the sex of the carrier parent.

Management options for these couples

• Prenatal genetic studies (amniocentesis or chorionic

villus sampling)

• In vitro fertilization (IVF) with preimplantation genetic

screening(PGT-A) Gamete donation (egg or sperm)

• Adoption

UTERINE ABNORMALITIES [86-91] — Uterine

abnormalities are managed surgically (hysteroscopically) if

correctable cause, such as a uterine septum, intrauterine

adhesions, or submucosal myoma.

There are no randomized trials evaluating pregnancy

outcome after surgical correction of uterine anomalies. In a

classic observational series, repair of septate uteri

reduced the abortion rate from 84 percent (before surgery)

to 12 percent (after surgery) using patients as their own

controls The value of prophylactic cervical cerclage in

women with a uterine anomaly, but no history of second

trimester pregnancy loss, is controversial. Cervical

cerclage is associated with potential hazards related to the

surgery and the risk of stimulating uterine contractions and

should be considered only in women who are likely to

benefit. Women with a history of second-trimester

miscarriage and suspected cervical weakness should be

monitored closely by serial cervical scans. In women with a

singleton pregnancy and a history of one second-trimester

miscarriage, an ultrasound-indicated cerclage should be

offered if a cervical length of 25 mm or less is detected by

transvaginal scan before 24 weeks of gestation. A

gestational carrier (surrogate) is an option for women with

irreparable uterine defects.

ANTIPHOSPHOLIPID SYNDROME [92]. — Aspirin and

heparin improve pregnancy outcome in women with APS with RPL.

LMWH appear to have additional qualities in preventing

adverse pregnancy outcome by their anti-inflammatory and

proangiogenic properties.

SUSPECTED IMMUNOLOGIC DYSFUNCTION [93-101]— No

alloimmune mechanism has been proven to cause RPL

.Immunologic treatments for unexplained RPL are not

effective, and may even be harmful as proven in systematic

reviews and should use only in the setting of a clinical

trial regulated by an Institutional Review Board.

• Paternal cell immunization

• Third party donor cell immunization

• Trophoblast membrane infusion

• Intravenous immunoglobulins (IV Ig)

• Glucocorticoids— Glucocorticoids have several

anti-inflammatory effects, including suppression of NK cell

activity, but do not appear to be effective for preventing

RPL. Steroids for treatment of RPL has been abandoned

because of uncertain efficacy and increase in complications,

such as preterm premature rupture of membranes, gestational

diabetes, and maternal hypertension

THYROID DYSFUNCTION AND DIABETES MELLITUS [102,103].

—

• Women with overt thyroid disease or diabetes mellitus

should be treated, as medically appropriate, since these

disorders can result in serious sequelae.

• Women with elevated serum thyroid peroxidase antibody

concentrations are at high risk of developing hypothyroidism

in the first trimester and autoimmune thyroiditis

postpartum, and should be followed appropriately

• Euthyroid women with high serum thyroid peroxidase

antibody concentrations may benefit from treatment with

levothyroxine (50 mcg daily) during pregnancy as it may

reduce the risk of miscarriage and preterm birth although

more trials are required.

POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME [104]. — The miscarriage

rate in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is 20 to

40 percent, higher than the baseline rate in the general

obstetric population Metformin has been used in women with

PCOS to decrease this risk, but the effectiveness of this

approach is unproven.

HYPERPROLACTINEMIA [105]. — Normal levels of

prolactin may play a significant role in maintaining early

pregnancy. A study of 64 hyperprolactinemic women with RPL

randomly assigned to bromocriptine therapy or no

bromocriptine found treatment was associated with a

significantly higher rate of successful pregnancy (86 versus

52 percent Prolactin levels during early pregnancy were

significantly greater in women who miscarried.

THROMBOPHILIA — Anticoagulation of women with

certain inherited thrombophilias may improve maternal

outcome (e.g., prevention of venous thromboembolism), but

controversial in RPL.

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR UNEXPLAINED RPL — [106]. A

significant proportion of cases of RPL remain unexplained

despite detailed investigation. These women can be reassured

that the prognosis for a successful future pregnancy with

supportive care alone is almost 75%.

Several unproven treatments are often offered for

unexplained RPL

• Lifestyle modification — Eliminating use of tobacco

products, alcohol, and caffeine and reduction in body mass

index (for obese women) may improve chances of live birth

• Progesterone [106-110] — Therapeutic effect of

progesterone may be related to immune modulation it is

possible that earlier initiation of progesterone, such as

during the luteal phase, may improve outcome as shown by

small studies.

Older metaanalysis including smaller heterogeneous

studies confounded by fetal factors showed a beneficial

effect but a large trial comparing first-trimester vaginal

progesterone therapy or placebo showed no significant

difference

• Human menopausal gonadotropin [111] — an

observational study reported that controlled ovarian

stimulation with human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG)

appeared effective for endometrial defects in women with RPL

likely by correction of a luteal phase defect or a thicker

endometrium, leading to a better implantation.

• Human chorionic gonadotropin (118) — HCG is

critical to early pregnancy, ensuring active maintenance of

steroid production from the corpus luteum and for

endometrial preparation to facilitate implantation. Although

HCG has shown to improve LBR in systematic reviews but there

is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of hCG to

prevent pregnancy loss in women with a history of

unexplained RPL. However hCG also had detrimental effects on

decidualization in vitro. There are evidences both for and

against its use, so it should be offered to women only

within a research trial. Large randomized controlled trials

to identify subgroups which are likely to benefit are

needed.

• In vitro fertilization and preimplantation genetic

diagnosis (PGT-A) [112-116]. — Studies evaluating the

value of in vitro fertilization (IVF) in women with RPL have

yielded mixed results. Embryos of women with unexplained RPL

have a higher incidence of aneuploidy. In a retrospective

cohort study of 300 women with RPL, the pregnancy, live

birth, and miscarriage rates were similar for women who

underwent IVF with preimplantation screening (PGS) and women

who elected expectant management other drawbacks include

need for IVF, cost involved and issues related to PGT-A like

mosaicism.

• Oocyte donation [117] — Poor quality oocytes may

be responsible for 25 percent of pregnancy losses Ovum

donation can overcome this problem and has been associated

with a live birth rate of 88 percent in women with RPL.

• Surrogacy — a gestational carrier may be

considered in RPL not associated with recurrent embryonic

aneuploidy or obvious intrinsic gamete factors (e.g., single

gene defects, diminished oocyte and embryo quality).

FUTURE PREGNANCY PROGNOSIS

• Continued pregnancy loss [119,120] — the

greatest risk of recurrent loss occurs during the period up

to the time of previous miscarriage. The likelihood of

successful pregnancy in women with a history of recurrent

pregnancy loss (RPL) was 67-75 percent at 5 years.

Increasing maternal age and number of miscarriages are

associated with a poorer prognosis.

• Other obstetric issues. [121,122].— Women with a

history of RPL who become pregnant may be at higher risk for

developing fetal growth restriction and premature delivery,

but not for gestational hypertension or diabetes

Table IV: Comparison of Guidelines for the

Investigation and Treatment of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss

|

Investigation or Treatment |

ASRM Guidelines |

RCOG Guidelines |

ESHRE Guidelines(2017) |

|

Parental karyotyping |

Recommended |

Recommended only if POC shows unbalanced

translocation |

Recommended only after individual risk

assessment |

|

POC karyotyping |

Recommended |

Recommended after 2 miscarriages |

Trials required |

|

aCGH preferable |

|

APS assessment (ACA and LA) |

Recommended |

Recommended |

Recommended |

|

Treatment of APS with heparin and aspirin |

Recommended |

Recommended |

Recommended |

|

Thyroid function |

Recommended |

Recommended |

Recommended |

|

Treatment of Overt Hypothyroidism with

levothyroxine |

|

Recommended |

Recommended |

|

Treatment of Subclinical hypothyroidism |

|

Recommended |

Need more trials, Inconsistent evidence |

|

Glucose intolerance testing in PCO |

|

Insufficient evidence |

Not Recommended for RPL prognosis |

|

Metformin in RPL with PCO |

|

Insufficient evidence |

Insufficient evidence |

|

Prolactin estimation |

Recommended |

|

Not recommended in absence of clinical signs |

|

Bromocriptine for Hyperprolactinemia |

|

|

Recommended |

|

Ovarian reserve testing |

|

|

Insufficient evidence |

|

Uterine cavity assessment |

Insufficient evidence |

Recommended |

Recommended (3D US/Sono HG)) |

|

Resection of uterine septum |

Can be considered |

Insufficient evidence |

More trials needed |

|

Hysteroscopic polypectomy/Myomectomy |

Can be considered |

|

Not recommended |

|

Hysteroscopic adhesiolysis |

Can be considered |

|

Insufficient evidence |

|

Serial cervical USG surveillance in suspected

incompetence |

|

Recommended |

Recommended |

|

Cervical cerclage for second trimester loss |

|

Ultrasound indicated |

|

|

Luteal Phase Insufficiency testing |

Insufficient evidence |

Not recommended |

Not recommended |

|

Progesterone supplementation |

Insufficient evidence |

Insufficient evidence |

Insufficient evidence- More RCTs required |

|

hCG supplementation |

|

Insufficient evidence |

Insufficient evidence |

|

Bacterial vaginosis |

Not recommended |

Insufficient evidence |

|

|

Hereditary thrombophilias |

Not recommended |

Recommended for second trimester losses |

Recommended in research settings or if

additional risk factors |

|

Anticoagulants for hereditary thrombophilia |

|

Insufficient evidence |

Insufficient evidence |

|

TORCH Testing |

Not recommended |

Not recommended |

Not recommended |

|

Alloimmune testing |

Not recommended |

Not recommended |

Insufficient evidence |

|

(HLA, Peripheral blood NK cells, Cytokine

polymorphism) |

|

ANA |

|

|

For explanatory purpose |

|

Immunotherapy(LIT/IVIg) |

Not recommended |

Not recommended |

Insufficient evidence |

|

Tender loving care |

Recommended |

Insufficient evidence |

Recommended |

|

Obesity, smoking, alcohol |

|

|

Recommended |

|

Folic acid for hyperhomocysteinemia |

|

|

Insufficient evidence |

|

Preconceptional Vitamin D supplementation |

|

|

Recommended based on significant prevalence in

RPL |

|

Steroids |

Not recommended |

Not recommended |

Not recommended |

|

G CSF / Intralipids /

Heparin/Aspirin/Endometrial scratching for

Unexplained RPL |

|

|

Not recommended |

|

Male partner life style factors. |

|

|

Recommended |

|

Assessing sperm DNA fragmentation |

Insufficient evidence |

|

Considered for explanatory purposes, based on

indirect evidence |

|

Antioxidants for men |

|

|

Insufficient evidence |

ASRM: American Society of Reproductive Medicine; RCOG: Royal

College of Obstetricians; ESHRE: European Society of Human

Reproduction and Embryology

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

●Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) refers to the occurrence

of three or more consecutive losses of clinically recognized

pregnancies prior to the 20th week of gestation (excluding

ectopic, molar, and biochemical pregnancies). It may be

primary or secondary.

●0.4 to 1 percent of women have three consecutive pregnancy

losses.

● Chromosomal abnormalities are the most common cause of

sporadic early pregnancy loss (50 %). 3 to 5 % of couples

with RPL have a major chromosomal rearrangement (vs. 0.7

percent of the general population); usually a balanced

translocation.

●Uterine abnormalities, both acquired and congenital have

been reported to be responsible for 10 to 50 percent of RPL

in small studies.

●Pregnancy loss is one of the diagnostic criteria for

antiphospholipid syndrome.

●Endocrine factors may account for some cases of RPL.

●There is no strong evidence showing a relationship between

RPL and occupational factors, stress, or mild exposure to

most environmental chemicals.

●RPL typically occurs at a similar gestational age in

consecutive pregnancies. The recurrence risk increases as

gestational age at the time of loss increases.

●Evaluation of women for RPL may be recommended after two or

three consecutive miscarriages depending on other factors

like age.

●A detailed history and physical examination should guide

the clinician regarding probable etiology and tailor

diagnostic investigations and management in RPL.

●The following initial evaluation may

be recommended as per need:

•Sonohysterography/3D USG for assessment of uterine

abnormalities

•Anticardiolipin antibody (IgG and IgM) titre and lupus

anticoagulant performed twice, six to eight weeks apart

•Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyroid peroxidase

antibodies

•Parental karyotype and karyotype of the abortus if the

above examinations are normal.

Additional testing depends upon the diagnosis suggested by

the history, physical examination, and laboratory results.

• Couples with chromosomal abnormalities in one or both

partners or the abortus are generally referred for genetic

counselling.

• Correctable uterine abnormalities such as a uterine septum

or intrauterine adhesions may be managed hysteroscopically.

• For women with unexplained RPL, there is not enough

evidence that use of vaginal progesterone or HCG improves

live birth rates.

• Immunotherapy or glucocorticoids are not effective for RPL

and may be harmful.

• Women with hyperprolactinemia and RPL should be treated.

• For unexplained RPL low risk, simple, and less expensive

interventions should be preferred over more complex and

expensive options.

• Women with a history of RPL who become pregnant may be at

higher risk for developing fetal growth restriction and

premature delivery.

REFERENCES

1. Christiansen OB, Nybo Andersen AM, Bosch E, et al.

Evidence-based investigations and treatments of recurrent

pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril 2005; 83:821.

2. Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive

Medicine. Definitions of infertility and recurrent pregnancy

loss: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2013; 99:63.

3. Jauniaux E, Farquharson RG, Christiansen OB, Exalto N.

Evidence-based guidelines for the investigation and medical

treatment of recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod 2006;

21:2216.

4. Greentop Guideline 17. Recurrent Miscarriage,

investigation and treatment of couples. Royal College of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2011.

5. Kolte AM, van Oppenraaij RH, Quenby S, et al.

Non-visualized pregnancy losses are prognostically important

for unexplained recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod 2014;

29:931.

6. Kolte AM, Bernardi LA, Christiansen OB, et al.

Terminology for pregnancy loss prior to viability: a

consensus statement from the ESHRE early pregnancy special

interest group. Hum Reprod 2015; 30:495.

7. Ansari AH, Kirkpatrick B. Recurrent pregnancy loss. An

update. J Reprod Med 1998; 43:806.

8. Paukku M, Tulppala M, Puolakkainen M, et al. Lack of

association between serum antibodies to Chlamydia

trachomatis and a history of recurrent pregnancy loss.

Fertil Steril 1999; 72:427.

9. Salat-Baroux J. [Recurrent spontaneous abortions]. Reprod

Nutr Dev 1988; 28:1555.

10. Edmonds DK, Lindsay KS, Miller JF, et al. Early

embryonic mortality in women. Fertil Steril 1982; 38:447.

11. Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O'Connor JF, et al. Incidence of

early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1988; 319:189.

12. Nybo Andersen AM, Wohlfahrt J, Christens P, et al.

Maternal age and fetal loss: population based register

linkage study. BMJ 2000; 320:1708.

13. Stirrat GM. Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet 1990; 336:673.

14. Franssen MT, Korevaar JC, Leschot NJ, et al. Selective

chromosome analysis in couples with two or more

miscarriages: case-control study. BMJ 2005; 331:137.

15. De Braekeleer M, Dao TN. Cytogenetic studies in couples

experiencing repeated pregnancy losses. Hum Reprod 1990;

5:519.

16. Carp H, Toder V, Aviram A, Daniely M, Mashiach S, Barkai

G. Karyotype of the abortus in recurrent miscarriage. Fertil

Steril 2001;75:678–82

17. Ogasawara M, Aoki K, Okada S, Suzumori K. Embryonic

karyotype of abortuses in relation to the number of previous

miscarriages. Fertil Steril 2000; 73:300–4.)

18. Lockwood CJ, Romero R, Feinberg RF, Clyne LP, Coster B,

Hobbins JC. The prevalence and biologic significance of

lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies in a

general obstetric population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;

161:369–73?

19. Pattison NS, Chamley LW, McKay EJ, Liggins GC, Butler

WS. Antiphospholipid antibodies in pregnancy: prevalence and

clinical association.Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1993; 100:909–13.

20. Hill JA, Choi BC. Maternal immunological aspects of

pregnancy success and failure. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 2000;

55:91.

21. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

ACOG practice bulletin. Management of recurrent pregnancy

loss. Number 24, February 2001.

22. Dosiou C, Giudice LC. Natural killer cells in pregnancy

and recurrent pregnancy loss: endocrine and immunologic

perspectives. Endocr Rev 2005; 26:44.

23. Laird SM, Tuckerman EM, Cork BA, et al. A review of

immune cells and molecules in women with recurrent

miscarriage. Hum Reprod Update 2003; 9:163.

24. Sotiriadis A, Makrigiannakis A, Stefos T, et al.

Fibrinolytic defects and recurrent miscarriage: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2007; 109:1146.

25. Laude I, Rongières-Bertrand C, Boyer-Neumann C, et al.

Circulating procoagulant microparticles in women with

unexplained pregnancy loss: a new insight. Thromb Haemost

2001; 85:18.

26. Acién P, Acién M, Sánchez-Ferrer M. Complex

malformations of the female genital tract. New types and

revision of classification. Hum Reprod 2004; 19:2377.

27. Devi Wold AS, Pham N, Arici A. Anatomic factors in

recurrent pregnancy loss. Semin Reprod Med 2006; 24:25.

28. Homer HA, Li TC, Cooke ID. The septate uterus: a review

of management and reproductive outcome. Fertil Steril 2000;

73:1.

29. Proctor JA, Haney AF. Recurrent first trimester

pregnancy loss is associated with uterine septum but not

with bicornuate uterus. Fertil Steril 2003; 80:1212.

30. Paulson RJ. Hormonal induction of endometrial

receptivity. Fertil Steril 2011; 96:530.

31. Lessey BA. Assessment of endometrial receptivity. Fertil

Steril 2011; 96:522.

32. Li TC, Tuckerman EM, Laird SM. Endometrial factors in

recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod Update 2002; 8:43.

33. Lucas ES, Dyer NP, Murakami K, et al. Loss of

Endometrial Plasticity in Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Stem

Cells 2016; 34:346.

34. Savitz DA, Sonnenfeld NL, Olshan AF. Review of

epidemiologic studies of paternal occupational exposure and

spontaneous abortion. Am J Ind Med 1994; 25:361.

35. Bellver J, Rossal LP, Bosch E, et al. Obesity and the

risk of spontaneous abortion after oocyte donation. Fertil

Steril 2003; 79:1136.

36. Gopalkrishnan K, Padwal V, Meherji PK, et al. Poor

quality of sperm as it affects repeated early pregnancy

loss. Arch Androl 2000; 45:111.

37. Carrell DT, Wilcox AL, Lowy L, et al. Elevated sperm

chromosome aneuploidy and apoptosis in patients with

unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol 2003;

101:1229.

38. Zidi-Jrah I, Hajlaoui A, Mougou-Zerelli S, et al.

Relationship between sperm aneuploidy, sperm DNA integrity,

chromatin packaging, traditional semen parameters, and

recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril 2016; 105:58.

39. . Leitich H,Kiss H.Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis and

intermediate flora as risk factors for adverse pregnancy

outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;

21:375–90.

40. Llahi-Camp JM, Rai R, Ison C, Regan L,Taylor-Robinson D.

Association of bacterial vaginosis with a history of second

trimester miscarriage. Hum Reprod 1996; 11:1575–8.

41. Ralph SG, Rutherford AJ, Wilson JD. Influence of

bacterial vaginosis on conception and miscarriage in the

first trimester: cohort study. BMJ 1999; 319:220–3.

42. Trout SW, Seifer DB. Do women with unexplained recurrent

pregnancy loss have higher day 3 serum FSH and estradiol

values? Fertil Steril 2000; 74:335.

43. Bombell S, McGuire W. Cytokine polymorphisms in women

with recurrent pregnancy loss: meta-analysis. Aust N Z J

Obstet Gynaecol 2008; 48:147.

44. Schweikert A, Rau T, Berkholz A, et al. Association of

progesterone receptor polymorphism with recurrent abortions.

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004; 113:67.

45. Bahia W, Finan RR, Al-Mutawa M, et al. Genetic variation

in the progesterone receptor gene and susceptibility to

recurrent pregnancy loss: a case-control study. BJOG 2018;

125:729.

46. Clark DA, Daya S, Coulam CB, Gunby J. Implication of

abnormal human trophoblast karyotype for the evidence-based

approach to the understanding, investigation, and treatment

of recurrent spontaneous abortion. The Recurrent Miscarriage

Immunotherapy Trialists Group. Am J Reprod Immunol 1996;

35:495?

47. Hassold T, Jacobs PA, Pettay D. Cytogenetic studies of

couples with repeated spontaneous abortions of known

karyotype. Genet Epidemiol 1988; 5:65.

48. Schaeffer AJ, Chung J, Heretis K, et al. Comparative

genomic hybridization-array analysis enhances the detection

of aneuploidies and submicroscopic imbalances in spontaneous

miscarriages. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 74:1168?

49. Fritz B, Hallermann C, Olert J, et al. Cytogenetic

analyses of culture failures by comparative genomic

hybridisation (CGH)-Re-evaluation of chromosome aberration

rates in early spontaneous abortions. Eur J Hum Genet 2001;

9:539.

50. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 446: array comparative

genomic hybridization in prenatal diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol

2009; 114:1161.

51. Goldberg JM, Falcone T, Attaran M. Sonohysterographic

evaluation of uterine abnormalities noted on

hysterosalpingography. Hum Reprod 1997; 12:2151.

52. Soares SR, Barbosa dos Reis MM, Camargos AF. Diagnostic

accuracy of sonohysterography, transvaginal sonography, and

hysterosalpingography in patients with uterine cavity

diseases. Fertil Steril 2000; 73:406.

53. Keltz MD, Olive DL, Kim AH, Arici A. Sonohysterography

for screening in recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril

1997; 67:670.

54. Reuter KL, Daly DC, Cohen SM. Septate versus bicornuate

uteri: errors in imaging diagnosis. Radiology 1989; 172:749.

55. Malhotra N, Sood M. Role of hysteroscopy in infertile

women. J Indian Med Assoc 1997; 95:499, 525.

56. Pellerito JS, McCarthy SM, Doyle MB, et al. Diagnosis of

uterine anomalies: relative accuracy of MR imaging,

endovaginal sonography, and hysterosalpingography. Radiology

1992; 183:795.

57. Bermejo C, Martínez Ten P, Cantarero R, et al.

Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of Müllerian

duct anomalies and concordance with magnetic resonance

imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2010; 35:593.

58. Roubey RA. Update on antiphospholipid antibodies. Curr

Opin Rheumatol 2000; 12:374.

59. Vinatier D, Dufour P, Cosson M, Houpeau JL.

Antiphospholipid syndrome and recurrent miscarriages. Eur J

Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001; 96:37.

60. Coulam CB, Branch DW, Clark DA et al. American Society

for Reproductive Immunology report of the Committee for

establishing criteria for diagnosis of reproductive

autoimmune syndrome. Am J Reprod Immunol 1999; 41:121–32?

61. Negro R, Schwartz A, Gismondi R, et al. Increased

pregnancy loss rate in thyroid antibody negative women with

TSH levels between 2.5 and 5.0 in the first trimester of

pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95:E44.

62. Chen L, Hu R. Thyroid autoimmunity and miscarriage: a

meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011; 74:513.

63. Thangaratinam S, Tan A, Knox E, et al. Association

between thyroid autoantibodies and miscarriage and preterm

birth: meta-analysis of evidence. BMJ 2011; 342:d2616.

64. Cervera R, Balasch J. Autoimmunity and recurrent

pregnancy losses. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2010; 39:148.

65. Harger JH, Rabin BS, Marchese SG. The prognostic value

of antinuclear antibodies in women with recurrent pregnancy

losses: a prospective controlled study. Obstet Gynecol 1989;

73:419.

66. Coulam CB. Immunologic tests in the evaluation of

reproductive disorders: a critical review. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1992; 167:1844?

67. Laird SM, Tuckerman EM, Cork BA, et al. A review of

immune cells and molecules in women with recurrent

miscarriage. Hum Reprod Update 2003; 9:163.

68. Clark DA. Is there any evidence for immunologically

mediated or immunologically modifiable early pregnancy

failure? J Assist Reprod Genet 2003; 20:63.

69. Moffett A, Regan L, Braude P. Natural killer cells,

miscarriage, and infertility. BMJ 2004; 329:1283–5.

70. Wold AS, Arici A. Natural killer cells and reproductive

failure. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2005; 17:237–41.

71. Rai R, Sacks G, Trew G. Natural killer cells and

reproductive failure – theory, practice and prejudice. Hum

Reprod 2005; 20:1123–6.

72. Le Bouteiller P, Piccinni MP. Human NK cells in pregnant

uterus: why there? Am J Reprod Immunol 2008; 59:401–6?

73. Tuckerman E, Laird SM, Prakash A, LiTC. Prognostic value

of the measurement of uterine natural killer cells in the

endometrium of women with recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod

2007; 22:2208–13.

74. Bombell S, McGuire W. Cytokine polymorphisms in women

with recurrent pregnancy loss: meta-analysis. Aust N Z J

Obstet Gynaecol 2008; 48:147–54.

75. Ogasawara M, Kajiura S, Katano K, et al. Are serum

progesterone levels predictive of recurrent miscarriage in

future pregnancies? Fertil Steril 1997; 68:806.

76. Peters AJ, Lloyd RP, Coulam CB. Prevalence of

out-of-phase endometrial biopsy specimens. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1992; 166:1738?

77. Harger JH, Archer DF, Marchese SG, et al. Etiology of

recurrent pregnancy losses and outcome of subsequent

pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 1983; 62:574.

78. Liddell HS, Pattison NS, Zanderigo A. Recurrent

miscarriage--outcome after supportive care in early

pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1991; 31:320.

79. Clifford K, Rai R, Regan L. Future pregnancy outcome in

unexplained recurrent first trimester miscarriage. Hum

Reprod 1997; 12:387.

80. Laurino MY, Bennett RL, Saraiya DS, et al. Genetic

evaluation and counselling of couples with recurrent

miscarriage: recommendations of the National Society of

Genetic Counsellors. J Genet Couns 2005; 14:165.

81. Egozcue J, Santaló J, Giménez C, et al. Preimplantation

genetic diagnosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2000; 166:21.

82. Munné S, Cohen J, Sable D. Preimplantation genetic

diagnosis for advanced maternal age and other indications.

Fertil Steril 2002; 78:234.

83. Werlin L, Rodi I, DeCherney A, et al. Preimplantation

genetic diagnosis as both a therapeutic and diagnostic tool

in assisted reproductive technology. Fertil Steril 2003;

80:467.

84. Otani T, Roche M, Mizuike M, et al. Preimplantation

genetic diagnosis significantly improves the pregnancy

outcome of translocation carriers with a history of

recurrent miscarriage and unsuccessful pregnancies. Reprod

Biomed Online 2006; 13:869.

85. Mastenbroek S, Twisk M, van Echten-Arends J, et al. In

vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic screening.

N Engl J Med 2007; 357:9.

86. March CM, Israel R. Gestational outcome following

hysteroscopic lysis of adhesions. Fertil Steril 1981;

36:455.

87. Kutteh WH. Antiphospholipid antibody-associated

recurrent pregnancy loss: treatment with heparin and

low-dose aspirin is superior to low-dose aspirin alone. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174:1584?

88. March CM, Israel R. Hysteroscopic management of

recurrent abortion caused by septate uterus. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1987; 156:834?

89. Patton PE, Novy MJ, Lee DM, Hickok LR. The diagnosis and

reproductive outcome after surgical treatment of the

complete septate uterus, duplicated cervix and vaginal

septum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 190:1669?

90. Mollo A, De Franciscis P, Colacurci N, et al.

Hysteroscopic resection of the septum improves the pregnancy

rate of women with unexplained infertility: a prospective

controlled trial. Fertil Steril 2009; 91:2628.

91. Tomaževič T, Ban-Frangež H, Virant-Klun I, et al.

Septate, subseptate and arcuate uterus decrease pregnancy

and live birth rates in IVF/ICSI. Reprod Biomed Online 2010;

21:700.

92. Recurrent Pregnancy Loss, Guideline of the European

Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, NOVEMBER 2017

ESHRE Early Pregnancy Guideline Development Group

93. Wong LF, Porter TF, Scott JR. Immunotherapy for

recurrent miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;

CD000112.

94. Hutton B, Sharma R, Fergusson D, et al. Use of

intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of recurrent

miscarriage: a systematic review. BJOG 2007; 114:134.

95. Laskin CA, Bombardier C, Hannah ME, et al. Prednisone

and aspirin in women with autoantibodies and unexplained

recurrent fetal loss. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:148.

96. Regan L, Rai R. Epidemiology and the medical causes of

miscarriage. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol

2000; 14:839.

97. Ogasawara M, Aoki K. Successful uterine steroid therapy

in a case with a history of ten miscarriages. Am J Reprod

Immunol 2000; 44:253?

98. Christiansen OB, Larsen EC, Egerup P, et al. Intravenous

immunoglobulin treatment for secondary recurrent

miscarriage: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled

trial. BJOG 2015; 122:500.

99. Clark DA, Coulam CB, Stricker RB. Is intravenous

immunoglobulins (IVIG) efficacious in early pregnancy

failure? A critical review and meta-analysis for patients

who fail in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF). J

Assist Reprod Genet 2006; 23:1.

100. Ata B, Tan SL, Shehata F, et al. A systematic review of

intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of unexplained

recurrent miscarriage. Fertil Steril 2011; 95:1080.

101. Egerup P, Lindschou J, Gluud C, et al. The Effects of

Intravenous Immunoglobulins in Women with Recurrent

Miscarriages: A Systematic Review of Randomised Trials with

Meta-Analyses and Trial Sequential Analyses Including

Individual Patient Data. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0141588.

102. Marqusee E, Hill JA, Mandel SJ. Thyroiditis after

pregnancy loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82:2455.

103. Negro R, Formoso G, Mangieri T, et al. Levothyroxine

treatment in euthyroid pregnant women with autoimmune

thyroid disease: effects on obstetrical complications. J

Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:2587.

104. Glueck CJ, Wang P, Goldenberg N, Sieve-Smith L.

Pregnancy outcomes among women with polycystic ovary

syndrome treated with metformin. Hum Reprod 2002; 17:2858.

105. Hirahara F, Andoh N, Sawai K, et al. Hyperprolactinemic

recurrent miscarriage and results of randomized

bromocriptine treatment trials. Fertil Steril 1998; 70:246.

106. Coomarasamy A, Williams H, Truchanowicz E, et al. A

Randomized Trial of Progesterone in Women with Recurrent

Miscarriages. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2141.

107. Haas DM, Ramsey PS. Progestogen for preventing

miscarriage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; CD003511.

108. Coomarasamy A, Truchanowicz EG, Rai R. Does first

trimester progesterone prophylaxis increase the live birth

rate in women with unexplained recurrent miscarriages? BMJ

2011; 342:d1914.

109. Saccone G, Schoen C, Franasiak JM, et al.

Supplementation with progestogens in the first trimester of

pregnancy to prevent miscarriage in women with unexplained

recurrent miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis

of randomized, controlled trials. Fertil Steril 2017;

107:430.

110. Choi BC, Polgar K, Xiao L, Hill JA. Progesterone

inhibits in-vitro embryotoxic Th1 cytokine production to

trophoblast in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum

Reprod 2000; 15 Suppl 1:46.

111. Li TC, Ding SH, Anstie B, et al. Use of human

menopausal gonadotropins in the treatment of endometrial

defects associated with recurrent miscarriage: preliminary

report. Fertil Steril 2001; 75:434.

112. Balasch J, Creus M, Fabregues F, et al. In-vitro

fertilization treatment for unexplained recurrent abortion:

a pilot study. Hum Reprod 1996; 11:1579.

113. Pellicer A, Rubio C, Vidal F, et al. In vitro

fertilization plus preimplantation genetic diagnosis in

patients with recurrent miscarriage: an analysis of

chromosome abnormalities in human preimplantation embryos.

Fertil Steril 1999; 71:1033.

114. Simón C, Rubio C, Vidal F, et al. Increased chromosome

abnormalities in human preimplantation embryos after

in-vitro fertilization in patients with recurrent

miscarriage. Reprod Fertil Dev 1998; 10:87.

115. Raziel A, Herman A, Strassburger D, et al. The outcome

of in vitro fertilization in unexplained habitual aborters

concurrent with secondary infertility. Fertil Steril 1997;

67:88.

116. Murugappan G, Shahine LK, Perfetto CO, et al. Intent to

treat analysis of in vitro fertilization and preimplantation

genetic screening versus expectant management in patients

with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod 2016; 31:1668.

117. Remohí J, Gallardo E, Levy M, et al. Oocyte donation in

women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod 1996;

11:2048.

118. Morley LC, Simpson N, Tang T. Human chorionic

gonadotrophin (hCG) for preventing miscarriage. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2013; 31; 1:CD008611.)

119. Lund M, Kamper-Jørgensen M, Nielsen HS, et al.

Prognosis for live birth in women with recurrent

miscarriage: what is the best measure of success? Obstet

Gynecol 2012; 119:37.

120. Brigham SA, Conlon C, Farquharson RG. A longitudinal

study of pregnancy outcome following idiopathic recurrent

miscarriage. Hum Reprod 1999; 14:2868.

121. Field K, Murphy DJ. Perinatal outcomes in a subsequent

pregnancy among women who have experienced recurrent

miscarriage: a retrospective cohort study. Hum Reprod 2015;

30:1239.

122. Jivraj S, Anstie B, Cheong YC, et al. Obstetric and

neonatal outcome in women with a history of recurrent

miscarriage: a cohort study. Hum Reprod 2001; 16:102.

|

|