| |

|

|

Author: Enrique Hernandez, MD, FACOG, FACS,

Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Director

of Gynecologic Oncology, Abraham Roth Professor of

Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Science, Professor

of Pathology, Temple University Hospital, Temple University

School of Medicine

Background

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) can

be benign or malignant. Histologically, it is classified

into hydatidiform mole, invasive mole (chorioadenoma

destruens), choriocarcinoma, and placental site

trophoblastic tumor (PSTT). Those that invade locally or

metastasize are collectively known as gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN). Hydatidiform mole is the most

common form of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (see

Image 1). While invasive mole and choriocarcinoma are

malignant, a hydatidiform mole can behave in a malignant or

benign fashion.

No methods exist to accurately predict the

clinical behavior of a hydatidiform mole by histopathology.

The clinical course is defined by the patient's serum human

chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) curve after evacuation of the

mole. In 80% of patients with a benign hydatidiform mole,

serum HCG titers steadily drop to normal within 8-12 weeks

after evacuation of the molar pregnancy. In the other 20% of

patients with a malignant hydatidiform mole, serum HCG

titers either rise or plateau.

The official International Federation of

Gynecology and Obstetrics staging of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia is as follows:

-

Stage I – Confined to the uterus

-

Stage II – Limited to the genital

structures

-

Stage III – Lung metastases

-

Stage IV – Other metastases

Each stage is sub-classified further

according to a prognostic scoring index. If the risk factors

are unknown, no substage is assigned. If the prognostic

score is 7 or less, the substage is A (e.g., IIIA is equal

to lung metastasis with a prognostic score of 7 or less). If

the prognostic score is 8 or greater, the substage is B.

The currently used prognostic scoring index

is a modification of the World Health Organization (WHO)

classification. It provides points for the presence of a

number of prognostic factors, as follows:

-

Age 40 years or older = 1 point

-

Antecedent pregnancy terminated in

abortion = 1 point

-

Antecedent full-term pregnancy = 2 points

-

Interval of 4 months to less than 7

months between antecedent pregnancy and start of

chemotherapy = 1 point

-

Interval of 7-12 months between

antecedent pregnancy and start of chemotherapy = 2

points

-

Interval of more than 12 months between

antecedent pregnancy and start of chemotherapy = 4

points

-

Beta-HCG level in serum is 1000 mIU/mL

but less than 10,000 mIU/mL = 1 point

-

Beta-HCG level in serum is 10,000 mIU/mL

but less than 100,000 mIU/mL = 2 points

-

Beta-HCG level in serum is 100,000 mIU/mL

or greater = 4 points

-

Largest tumor is 3 cm but less than 5 cm

= 1 point

-

Largest tumor is 5 cm or greater = 2

points

-

Site of metastases is spleen or kidney =

1 point

-

Site of metastases is gastrointestinal

tract = 2 points

-

Site of metastases is brain or liver = 4

points

-

Number of metastases is 1-4 = 1 point

-

Number of metastases is 5-8 = 2 points

-

Number of metastases is more than 8 = 4

points

-

Prior chemotherapy with single drug = 2

points

-

Prior chemotherapy with multiple drugs =

4 points

Pathophysiology

Histologically, hydatidiform moles look like

placental tissue, but edema of the villi demonstrates

varying sizes. Proliferation of the trophoblast occurs, and

fetal blood vessels are lacking or are scarce.

If a fetus or fetal parts are present, this

is known as a partial or incomplete mole. Partial moles also

have malignant potential, but only 2% become malignant. An

invasive mole has the same histopathologic characteristics

of a hydatidiform mole, but invasion of the myometrium with

necrosis and hemorrhage occurs or pulmonary metastases are

present. Histologically, choriocarcinomas have no villi, but

they have sheets of trophoblasts and hemorrhage.

Choriocarcinomas are aneuploid and can be

heterozygous, depending on the type of pregnancy from which

the choriocarcinoma arose. If a hydatidiform mole preceded

the choriocarcinoma, the chromosomes are of paternal origin.

Maternal and paternal chromosomes are present if a term

pregnancy precedes the choriocarcinoma. Of choriocarcinomas,

50% are preceded by a hydatidiform mole, 25% by an abortion,

and the other 25% by a full-term pregnancy.

Placental site trophoblastic tumor is a rare

form of gestational trophoblastic neoplasm, with slightly

more than 200 cases reported in the literature. In patients

with PSTT, intermediate trophoblasts are found infiltrating

the myometrium without causing tissue destruction. The

intermediate trophoblasts contain human placental lactogen

(HPL). These patients have persistent low levels of serum

HCG (100-1000 mIU/mL). However, serum HCG titers as high as

58,000 mIU/ml have been reported in patients with placental

site trophoblastic tumors. The treatment of placental site

trophoblastic tumors is hysterectomy with ovarian

conservation. If the tumor recurs or metastases are present

at initial diagnosis, chemotherapy is administered with

variable results. Radiation therapy may provide local

control.

The most frequent sites of metastases of

malignant gestational trophoblastic neoplasm are the lungs,

lower genital tract, brain, liver, kidney, and

gastrointestinal tract.

Frequency

United States

Hydatidiform moles occur in 1 in 2000

deliveries, or 1 in 850 to 1 in 1300 pregnancies.

International

In Mexico, an incidence of 1 in 200

deliveries is reported, while an incidence of 1 in 120

deliveries is reported in Taiwan. Some believe these

international differences are due to differences in diet.

However, in some countries, these differences are due to

poor recording of the total number of deliveries, especially

if deliveries are normal and do not occur in a hospital.

Mortality/Morbidity

Patients who have a malignant hydatidiform

mole, an invasive mole, or a choriocarcinoma should undergo

a systematic search for metastases. Patients who have

metastases are classified as high-risk or low-risk according

to the National Institutes of Health classification. The

criteria for high-risk metastatic gestational trophoblastic

neoplasia include hepatic or brain metastasis, serum HCG

titers greater than 40,000 mIU/mL prior to the initiation of

chemotherapy, duration of disease longer than 4 months,

prior unsuccessful chemotherapy, and malignant gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia following a term pregnancy.

-

Patients with malignant non-metastatic or

metastatic low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

have an almost 100% probability of cure with

chemotherapy. The probability of cure after chemotherapy

for patients with metastatic high-risk gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia is approximately 75%.

-

The probability of a late recurrence

after the patient has been in remission (normal serum

beta-HCG titers) for 1 year is less than 1%.

Race

-

International reports are conflicting as

to whether ethnicity is an independent risk factor for

the development of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia.

-

In the United States, race does not

appear to be a risk factor.

Sex

Age

CLINICAL

History

-

Patients with a hydatidiform mole present

with signs and symptoms of pregnancy.

-

The most frequent symptom of

gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) is

abnormal uterine bleeding.

-

Patients have a history of

amenorrhea. Occasionally, the typical hydatid

vesicles (edematous villi) are passed through the

vagina.

-

Signs and symptoms of preeclampsia occur

in up to one third of patients.

-

Prolonged hyperemesis gravidarum is also

common.

-

Hyperthyroidism is found in up to 3% of

patients. This is due to the production of human molar

thyrotropin by the molar tissue and the similarities

between HCG and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

-

If metastases exist, signs and symptoms

associated with the metastatic disease, such as

hematuria, hemoptysis, abdominal pain, and neurologic

symptoms, may be present.

-

The more frequent use of early

obstetrical ultrasound has resulted in the earlier

diagnosis of hydatidiform mole prior to the onset of the

above signs and symptoms.

Physical

Suspect gestational trophoblastic

neoplasia when a positive pregnancy test result occurs

in the absence of a fetus.

Uterine size could be larger, smaller, or

equal to the estimated gestational age.

The identification of hydatid vesicles in

the vagina is diagnostic for hydatidiform mole.

Enlarged ovaries secondary to theca

lutein cysts are found in up to 20% of patients with

hydatidiform mole.

-

These cysts are the result of

stimulation of the ovaries by the high circulating

levels of HCG.

-

The cysts regress after evacuation of

the hydatidiform mole, but this process can take as

long as 12 weeks.

Causes

A hydatidiform mole occurs when a haploid

sperm fertilizes an egg that has no maternal chromosomes

and then duplicates its chromosomal complement.

-

Most complete hydatidiform moles are

46, XX, and all the chromosomes come from the male.

-

Of hydatidiform moles, 10-15% are 46,

XY. This occurs when 2 sperm, 1 carrying an X and

the other carrying a Y, fertilize an "empty" egg.

Partial moles are 69, XXY, and 2 sets of

chromosomes are of paternal origin.

Lab Studies

-

Serum HCG is elevated and frequently

higher than expected for the estimated gestational age.

A serum HCG greater than 100,000 mIU/mL should raise the

concern of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD).

-

A CBC count may help detect anemia

secondary to vaginal bleeding.

-

Liver enzymes may become elevated in the

presence of metastasis to the liver.

Imaging Studies

·

-

CT and MRI are recommended if the

patient has malignant gestational trophoblastic

neoplasia (hydatidiform mole with metastasis to the

lungs, choriocarcinoma, or persistent hydatidiform

mole).

-

The lungs, lower genital tract,

brain, liver, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract are

frequent sites of metastases.

Procedures

-

Evacuation of the uterus is performed

with suction and sharp curettage.

-

The tissue is sent for

histopathologic examination.

-

Examination reveals a hydatidiform

mole (complete or partial) or a choriocarcinoma.

-

Rarely is a histopathologic diagnosis of

an invasive mole made on a dilation and curettage (D&C)

specimen because this requires the identification of

destructive invasion of the myometrium by the

trophoblasts. Scant or no myometrium is recovered on a

D&C specimen.

Histological Findings

Complete hydatidiform moles have edematous

placental villi, hyperplasia of the trophoblasts, and lack

or scarcity of fetal blood vessels.

In the incomplete or partial hydatidiform

mole, scalloping of the villi and trophoblastic inclusions

occur within the villi. Fetal blood vessels are present.

In a hydropic degeneration of a normal

pregnancy, edema of the villi is present, but no

trophoblastic hyperplasia. Ghost villi may be observed.

The invasive mole has the same appearance as

the hydatidiform mole, but the myometrium is invaded with

the presence of hemorrhage and tissue necrosis.

Although the choriocarcinoma has no chorionic

villi, it has sheets of trophoblasts, hemorrhage, and

necrosis. In the placental site trophoblastic tumors,

intermediate trophoblasts are found between myometrial

fibers, without tissue necrosis.

TREATMENT

Medical Care

-

Emergency department care involves

starting intravenous (IV) fluids (crystalloids) and

sending blood for type and antibody screen. Rh-negative

patients should receive anti–RhD immune globulin, if not

already immunized.

-

Patients with benign gestational

trophoblastic disease (GTD) do not require medical

therapy. Because 20% of patients with hydatidiform mole

develop malignant disease, such as persistent

hydatidiform mole with or without metastasis, some have

suggested the use of a prophylactic dose of methotrexate

(MTX) in noncompliant patients. However, observing

patients with weekly serum HCG titers is preferable, and

only patients with rising or plateauing titers, as

occurs in patients with malignant gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN), should be treated with

chemotherapy.

-

Patients with malignant nonmetastatic

gestational trophoblastic neoplasia or metastatic

low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia are treated

with single-agent chemotherapy. Many in the United

States prefer MTX. However, actinomycin D can be used in

patients with poor liver function. During treatment, the

serum HCG titers are monitored every week. One

additional course of chemotherapy is administered after

a normal serum HCG titer. After 3-4 normal serum HCG

titers, the titers are followed once per month for 1

year. A switch from MTX to actinomycin D is made if the

patient receiving MTX for nonmetastatic or metastatic

low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia develops

rising or plateauing serum HCG titers.

-

Patients with high-risk metastatic

gestational trophoblastic neoplasia are subdivided into

2 groups: those with a WHO score of less than 8 and

those with a score of 8 or higher and a high risk of

therapy failure.

·

-

In patients with a WHO score of less

than 8, a combination of MTX, actinomycin D, and

cyclophosphamide can be used. This is known as the

MAC regimen. This chemotherapeutic regimen is

administered every 19-21 days (from day 1 of the

previous chemotherapy cycle) until the serum HCG

titers normalize. In patients with a low WHO score,

one additional course of MAC is administered after a

normal serum HCG titer. Some prefer to treat these

patients with single-agent chemotherapy (MTX or

actinomycin) because their chances of achieving a

cure are high.

-

Patients with WHO scores of 8 or

higher are treated with a combination of etoposide,

MTX, and actinomycin D administered in the first

week of a 2-week cycle and cyclophosphamide and

vincristine administered in the second week. This is

known as the EMA-CO regimen. Some substitute

cisplatin and etoposide for cyclophosphamide and

vincristine during the second week. This is known as

the EMA-CE regimen. Some reserve the EMA-CE regimen

for patients in whom EMA-CO fails. Two additional

courses of EMA-CO or EMA-CE are administered after a

normal serum HCG titer in very high-risk patients.

Patients with metastasis to the brain receive whole

brain irradiation (3000 cGy) in combination with

chemotherapy. Corticosteroids (Decadron) with

systemic effect are administered to reduce brain

edema. Patients with liver metastasis are considered

for liver irradiation (2000 cGy).

Surgical Care

·

-

To avoid excessive bleeding, oxytocin

is administered intravenously at the initiation of

the suctioning of the uterine contents.

-

The largest possible suction curette

is used, usually a 10F or 12F.

FOLLOW-UP

Further Outpatient Care

-

In patients with benign gestational

trophoblastic disease (GTD), who do not require

chemotherapy, obtain follow-up serum HCG titers once per

week until 3-4 normal values are obtained. Then, obtain

them once per month for 6 months. Have patients use

reliable contraception, such as oral contraceptives or

depot progesterone injections, during the period of

follow-up care.

-

Patients with malignant gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia should have follow-up serum HCG

titers once per week until 4 normal values are obtained.

Then, obtain them once per month for 1 year. Have

patients use a reliable method of contraception.

In/Out Patient Meds

-

During the period of follow-up care,

patients with gestational trophoblastic disease should

use a reliable method of contraception, such as oral

contraceptives or depot progesterone.

-

The serum HCG titers are critical in

monitoring the status of the disease, and a normal

intrauterine pregnancy interferes with this critical

monitoring tool.

Complications

Prognosis

-

Nonmetastatic gestational trophoblastic

neoplasia has a cure rate with chemotherapy of close to

100%.

-

Metastatic low-risk gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia has a cure rate with

chemotherapy of close to 100%.

-

Metastatic high-risk gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia has a cure rate with

chemotherapy of approximately 75%.

-

After 12 months of normal HCG titers,

less than 1% of patients with malignant gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia have recurrences.

Patient Education

-

The rate of occurrence of a repeat molar

pregnancy is approximately 1-2%.

-

The rate of occurrence of a repeat molar

pregnancy in a patient with a history of 2 previous

hydatidiform moles is approximately 10-20%.

-

The pregnancy rate after chemotherapy

with MTX and cyclophosphamide is 80%. Of women treated

with EMA-CO, 46% have had at least 1 live birth after

chemotherapy.

-

Patients who become pregnant after

treatment for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia should

have a pelvic ultrasound early during the pregnancy to

confirm that the pregnancy is normal.

MISCELLANEOUS

MULTIMEDIA

|

Media file 1: Histological section of a complete

hydatidiform mole stained with hematoxylin and

eosin. Villi of different sizes are present. The

large villous in the center exhibits marked edema

with a fluid-filled central cavity known as

cisterna. Marked proliferation of the trophoblasts

is observed. The syncytiotrophoblasts stain purple,

while the cytotrophoblasts have a clear cytoplasm

and bizarre nuclei. No fetal blood vessels are in

the mesenchyme of the villi. |

|

|

View

Full Size Image View

Full Size Image |

|

|

|

Media type: Photo |

|

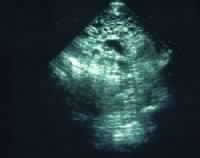

Media file 2: Real-time ultrasound image of a

hydatidiform mole. The dark circles of varying sizes

at the top center are the edematous villi. |

|

|

View Full Size Image View Full Size Image |

|

|

|

Media type: Image |

REFERENCES

-

Amir SM, Osathanondh R, Berkowitz RS,

Goldstein DP. Human chorionic gonadotropin and thyroid

function in patients with hydatidiform mole. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. Nov 15 1984;150(6):723-8.

-

Bandy LC, Clarke-Pearson DL, Hammond

CB. Malignant potential of gestational trophoblastic

disease at the extreme ages of reproductive life. Obstet

Gynecol. Sep 1984;64(3):395-9.

-

Barnard DE, Woodward KT, Yancy SG, et

al. Hepatic

metastases of choriocarcinoma: a report of 15 patients. Gynecol

Oncol. Sep 1986;25(1):73-83.

-

Batorfi J, Vegh G, Szepesi J, et al. How

long patients should be followed after molar pregnancy?

Analysis of serum hCG follow-up data. Eur J Obstet

Gynecol Reprod Biol. Jan 15 2004;112(1):95-7.

-

Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Chorionic

tumors. N Engl J Med. Dec 5 1996;335(23):1740-8.

-

Bovicelli L, Ghi T, Pilu G, et al. Prenatal

diagnosis of a complete mole coexisting with a

dichorionic twin pregnancy: case report. Hum Reprod. May 2004;19(5):1231-4.

-

Bower M, Newlands ES, Holden L, et al. EMA/CO

for high-risk gestational trophoblastic tumors: results

from a cohort of 272 patients. J Clin Oncol. Jul 1997;15(7):2636-43.

-

Chauhan S, Diamond MP, Johns DA. A case

of molar ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. Apr 2004;81(4):1140-1.

-

Cheung AN, Khoo US, Lai CY, et

al. Metastatic trophoblastic disease after an initial

diagnosis of partial hydatidiform mole: genotyping and

chromosome in situ hybridization analysis. Cancer. Apr

1 2004;100(7):1411-7. .

-

Escobar PF, Lurain JR, Singh DK, et

al. Treatment of high-risk gestational trophoblastic

neoplasia with etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin D,

cyclophosphamide, and vincristine chemotherapy. Gynecol

Oncol. Dec 2003;91(3):552-7.

-

FIGO Oncology Committee. FIGO staging for

gestational trophoblastic neoplasia 2000. Int J

Gynaecol Obstet. Jun 2002;77(3):285-7. .

-

Feltmate CM, Genest DR, Goldstein DP,

Berkowitz RS. Advances

in the understanding of placental site trophoblastic

tumor. J Reprod Med. May 2002;47(5):337-41.

-

Feltmate CM, Batorfi J, Fulop V, et al. Human

chorionic gonadotropin follow-up in patients with molar

pregnancy: a time for reevaluation. Obstet Gynecol. Apr 2003;101(4):732-6.

-

Fishman DA, Padilla LA, Keh P, et al. Management

of twin pregnancies consisting of a complete

hydatidiform mole and normal fetus. Obstet Gynecol. Apr 1998;91(4):546-50.

-

Foulmann K, Guastalla JP, Caminet N. What

is the best protocol of single-agent methotrexate

chemotherapy in nonmetastatic or low-risk metastatic

gestational trophoblastic tumors? A review of the

evidence. Gynecol Oncol. Jul 2006;102(1):103-10.

-

Garner EI, Lipson E, Bernstein MR, et

al. Subsequent

pregnancy experience in patients with molar pregnancy

and gestational trophoblastic tumor. J Reprod Med. May 2002;47(5):380-6.

-

Garner EI, Garrett A, Goldstein DP. Significance

of chest computed tomography findings in the evaluation

and treatment of persistent gestational trophoblastic

neoplasia. J Reprod Med. Jun 2004;49(6):411-4.

-

Ghaemmaghami F, Behtash N, Memarpour N,

et al. Evaluation and management of brain metastatic

patients with high-risk gestational trophoblastic

tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. Sep-Oct 2004;14(5):966-71. .

-

Goto S, Yamada A, Ishizuka T, Tomoda

Y. Development of post-molar trophoblastic disease after

partial molar pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol. Feb 1993;48(2):165-70.

-

Goto S, Ino K, Mitsui T, et al. Survival

rates of patients with choriocarcinoma treated with

chemotherapy without hysterectomy: effects of anticancer

agents on subsequent births. Gynecol Oncol. May 2004;93(2):529-35.

-

Grimes DA. Epidemiology of gestational

trophoblastic disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Oct

1 1984;150(3):309-18.

-

Hammond CB, Weed JC Jr, Currie JL. The

role of operation in the current therapy of gestational

trophoblastic disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Apr

1 1980;136(7):844-58.

-

Hancock BW, Tidy JA. Current management

of molar pregnancy. J Reprod Med. May 2002;47(5):347-54.

-

Hassadia A, Gillespie A, Tidy

J. Placental site trophoblastic tumour: clinical

features and management. Gynecol Oncol. Dec 2005;99(3):603-7.

-

Hoekstra AV, Keh P, Lurain JR. Placental

site trophoblastic tumor: a review of 7 cases and their

implications for prognosis and treatment. J Reprod

Med. Jun 2004;49(6):447-52.

-

Homesley HD, Blessing JA, Schlaerth J, et

al. Rapid escalation of weekly intramuscular

methotrexate for nonmetastatic gestational trophoblastic

disease: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol

Oncol. Dec 1990;39(3):305-8.

-

Kajii T, Kurashige H, Ohama K, Uchino

F. XY and XX complete moles: clinical and morphologic

correlations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Sep

1 1984;150(1):57-64.

-

Kashimura Y, Kashimura M, Sugimori H, et

al. Prophylactic chemotherapy for hydatidiform mole.

Five to 15 years follow-up. Cancer. Aug

1 1986;58(3):624-9.

-

Khanlian SA, Cole LA. Management of

gestational trophoblastic disease and other cases with

low serum levels of human chorionic gonadotropin. J

Reprod Med. Oct 2006;51(10):812-8.

-

Khanlian SA, Cole LA. Management of

gestational trophoblastic disease and other cases with

low serum levels of human chorionic gonadotropin. J

Reprod Med. Oct 2006;51(10):812-8.

-

Kohorn EI. Is lack of response to

single-agent chemotherapy in gestational trophoblastic

disease associated with dose scheduling or chemotherapy

resistance?. Gynecol Oncol. Apr 2002;85(1):36-9.

-

Kwon JS, Elit L, Mazurka J, et al. Weekly

intravenous methotrexate with folinic acid for

nonmetastatic gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Gynecol

Oncol. Aug 2001;82(2):367-70.

-

Lurain JR, Singh DK, Schink JC. Primary

treatment of metastatic high-risk gestational

trophoblastic neoplasia with EMA-CO chemotherapy. J

Reprod Med. Oct 2006;51(10):767-72.

-

Machtinger R, Gotlieb WH, Korach J, et

al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor: outcome of five

cases including fertility preserving management. Gynecol

Oncol. Jan 2005;96(1):56-61.

-

Mangili G, Garavaglia E, De Marzi P, et

al. Metastatic

placental site trophoblastic tumor. Report of a case

with complete response to chemotherapy. J Reprod Med. Mar 2001;46(3):259-62.

-

Massad LS, Abu-Rustum NR, Lee SS, Renta

V. Poor compliance with postmolar surveillance and

treatment protocols by indigent women. Obstet Gynecol. Dec 2000;96(6):940-4.

-

Matsui H, Iitsuka Y, Suzuka K, et

al. Risk of abnormal pregnancy completing chemotherapy

for gestational trophoblastic tumor. Gynecol Oncol. Feb 2003;88(2):104-7.

-

Matsui H, Iitsuka Y, Suzuka K, et

al. Salvage chemotherapy for high-risk gestational

trophoblastic tumor. J Reprod Med. Jun 2004;

49(6):438-42. .

-

Ngan HY, Chan FL, Au VW, et al. Clinical

outcome of micrometastasis in the lung in stage IA

persistent gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol

Oncol. Aug 1998;70(2):192-4.

-

Nigam S, Singhal N, Kumar Gupta S, et

al. Placental site trophoblastic tumor in a

postmenopausal female--a case report. Gynecol Oncol. May 2004;

93(2):550-3.

-

Olsen TG, Hubert PR, Nycum LR. Falsely

elevated human chorionic gonadotropin leading to

unnecessary therapy (1). Obstet Gynecol. Nov 2001;98(5

Pt 1):843-5.

-

Papadopoulos AJ, Foskett M, Seckl MJ, et

al. Twenty-five

years'' clinical experience with placental site

trophoblastic tumors. J Reprod Med. Jun 2002;47(6):460-4.

-

Roberts JP, Lurain JR. Treatment of

low-risk metastatic gestational trophoblastic tumors

with single-agent chemotherapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Jun 1996;174(6):1917-23;

discussion 1923-4.

-

Sand PK, Lurain JR, Brewer JI. Repeat

gestational trophoblastic disease. Obstet Gynecol. Feb 1984;63(2):140-4.

-

Schechter NR, Mychalczak B, Jones W,

Spriggs D. Prognosis of patients treated with

whole-brain radiation therapy for metastatic gestational

trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. Feb 1998;68(2):183-92.

-

Sebire NJ, Fisher RA, Foskett M, et al. Risk

of recurrent hydatidiform mole and subsequent pregnancy

outcome following complete or partial hydatidiform molar

pregnancy. BJOG. Jan 2003;110(1):22-6.

-

Smith HO, Kohorn E, Cole LA. Choriocarcinoma

and gestational trophoblastic disease. Obstet Gynecol

Clin North Am. Dec 2005;32(4):661-84.

-

Soper JT, Evans AC, Conaway MR, et

al. Evaluation of prognostic factors and staging in

gestational trophoblastic tumor. Obstet Gynecol. Dec 1994;84(6):969-73.

-

Soper JT, Clarke-Pearson DL, Berchuck A,

et al. 5-day methotrexate for women with metastatic

gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. Jul 1994;54(1):76-9.

-

Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP,

Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of

complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. Nov 1995;86(5):775-9.

-

Suzuka K, Matsui H, Iitsuka Y, et al. Adjuvant

hysterectomy in low-risk gestational trophoblastic

disease. Obstet Gynecol. Mar 2001;97(3):431-4.

-

Tidy JA, Gillespie AM, Bright N, et

al. Gestational trophoblastic disease: a study of mode

of evacuation and subsequent need for treatment with

chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. Sep 2000;78(3 Pt

1):309-12.

-

Xiang Y, Sun Z, Wan X, Yang X. EMA/EP

chemotherapy for chemorefractory gestational

trophoblastic tumor. J Reprod Med. Jun 2004;49(6):443-6.

|

|